The fact that they were so weak on stage showed how much power comes from within

Jenene Wooldridge, a Mi’kmaw author and the executive director of L’nuey in Epekwitk, wrote this First Person column (P.E.I.). For more information about CBC’s First Person stories, please see the FAQ.

When I was a kid, I didn’t see any Native American dancers or performers in the places I went. I didn’t hear about how they learned about our culture in the news. I didn’t see them being a part of celebrations. I didn’t see myself represented. I actually didn’t see any evidence of our culture anywhere.

So when my children were asked to participate in the 2023 Canada Winter Games opening ceremony on P.E.I., we saw it as an opportunity not only to share our culture with others, but also for other Indigenous people to see themselves reflected in the ceremonies and performances.

My kids have been dancing at gatherings and performing with the Mi’kmaq Heritage Actors since they could walk. They are now 9 and 11 years old. But seeing them at the Games connecting with Canadians from all over the country and showing off our culture through song and dance is something I’ll never forget.

The kids were ready for a big crowd at the opening ceremony, but what they got was a whole different thing. Thousands of people cheering, making noise, and clapping was, to say the least, overwhelming. Just before it was time to go on stage, both kids started to get nervous, and the fear of performing in front of such a big crowd took over.

Show tim

My daughter Taya was so afraid of crying on stage that she told me she didn’t want to perform at all.

I told her, “It’s okay if you cry on stage.” “We’re all people. We all have feelings, and you’re here to dance and show other people your culture. Just give it your best shot.”

Taya went on stage and tried to keep it together with lots of hugs, deep breaths, words of encouragement, and help from the stage manager, Sylvia. When an Alberta coach saw that Taya was having trouble, he promised to give her a tuque from his team.

Eventually, I saw both of my scared and nervous kids walk onto that big stage and comfort each other with pats on the back, nods of the head, and a few kind words. On that stage, a few tears were shed, but the show went on, and they danced.

When the drum started beating, they both put on their game faces. It was show time, so they did a dance they had done hundreds of times before: the traditional Mi’kmaq Ko’jua dance, in which they start with their feet in a V shape and tap one heel three times, then do the same thing with the other foot. Once they got into it, they added their arms and got into the rhythm. It’s a joyful dance connected to our ancestors.

The fringes of my son’s grass dance regalia swished back and forth as Taite danced. His porcupine head roach swayed with the movement. I heard the bells on his feet hit every beat perfectly. The bright colours on his regalia shone in the spotlight. Taya’s fancy shawl moved as gracefully as she did, glimmering under the lights surrounded on all sides by the thousands of people in the crowd. The fact that they were so weak on stage showed how much power comes from within..

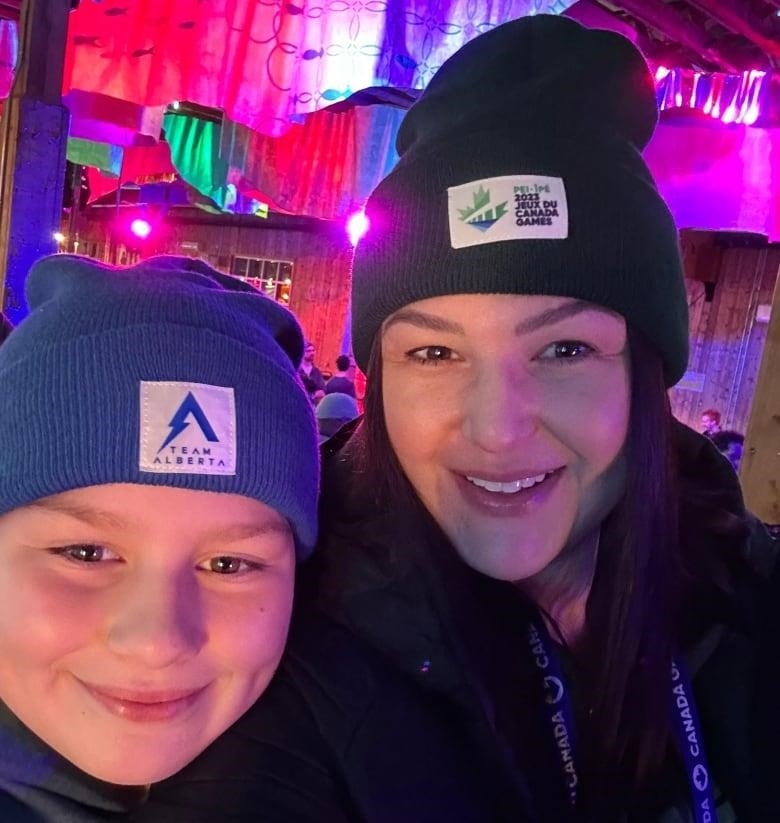

When they were done with their show, I welcomed them with open arms and tight hugs. And there was that coach from Alberta, waiting to give over his tuque. During the two weeks of the Canada Games, Taya wore it almost every day.

This is what it looks like to be brave

Taite and Taya were recognized everywhere they went during the two weeks that the Canada Games were on the Island. Athletes wanted to take pictures with them, and so many people, from volunteers to coaches to athletes, talked about how much the performance meant to them and how it changed them. With each new person they met, the kids beamed with pride as they talked about their performance and how big it was for them to be on stage at such a big venue.

Taite and Taya were asked to come back for the closing ceremony. This time, they knew more about what to expect. There were no tears. Instead, people talked, laughed, danced, and smiled a lot. They walked into the arena with confidence, Taite waving the Mi’kmaq flag and Taya dancing in a fancy shawl to the Mi’kmaq Heritage Actors singing the Mawiomi song.

I can’t describe how proud I felt when I saw those two young Mi’kmaw youth show off their culture for thousands of people across Canada to see, and how proud they were of themselves for doing such a hard thing.

If I only remember one thing from this, it is thatthisIs what courage and bravery look like: doing hard things despite tears and fear.

Do you want to write a First Person or Opinion piece for CBC Prince Edward Island?

We want to hear from Islanders or people with a strong connection to the Island who want to share a compelling personal story or their opinion on an issue that affects their community.You don’t have to be a professional writer — first-time contributors are always welcome.

Send us an email at [email protected] with your story.

See our FAQ for more information about First Person and Opinion submissions.