Scientists hope that their research at Wapusk will show that caribou need more protected areas in other parts of Canada

Wildlife scientists from two provinces are using motion-activated cameras to try to figure out why one caribou population in northern Manitoba seems to be stable while herds are shrinking almost everywhere else in Canada.

Researchers from Parks Canada, the University of Saskatchewan, and the Manitoba Métis Federation have been collecting pictures from 92 wildlife cameras in and around Wapusk National Park, a protected area in northern Manitoba along the coast of Hudson Bay, since 2022.

The park protects about 98% of the Cape Churchill caribou herd’s summer calving range. For decades, the herd’s population has been thought to be between 1,000 and 3,000 animals.

Wapusk also protects a part of the herd’s migration routes in the spring and fall. The herd spends the winter in relatively untouched forests outside the park.

Russell Turner, an ecosystems scientist at the park, said that Parks Canada and its research partners want to gather enough information to show a link between protecting habitats and keeping populations healthy.

“Almost every other caribou population in Canada is going down, so it’s too bad we don’t know why these caribou are stable, but it could be because they’re in a national park and are safe,” Russell said in an interview earlier this month outside of Churchill, Man.

Even though it seems like there should be a link between protection and population, Turner said that the Cape Churchill herd is unusual. It doesn’t spend the whole year in one ecological zone or another. Instead, it spends the winter in the boreal forest and the summer on the tundra.

Turner said, “We have a unique type that can live in both forests and deserts.” “It’s a small herd in Manitoba that hasn’t been studied much, so we don’t know very much about it.”

Remote camera

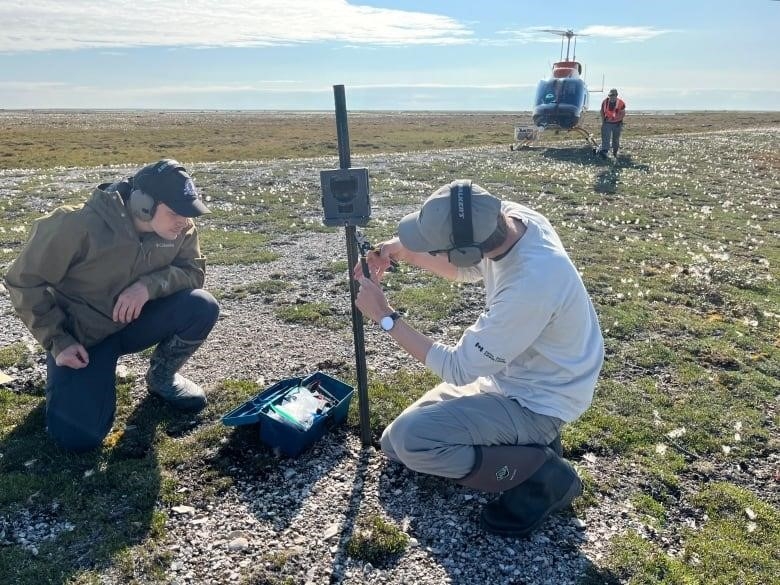

It’s not easy to get this information. Trail cameras are hard to set up in and around Wapusk because it is very cold and snowy in the winter, very wet in the summer, and there is no road access at any time of the year.

Parks Canada and its partners at the Métis Federation and the University of Saskatchewan take pictures with 92 cameras that are mounted on posts. They walk to places near a Wapusk research camp called Nester One to swap out batteries and memory cards.

Helicopters are used to fix other cameras. Some of these places are near Cape Churchill, where there is a sandbar called “the lounge” where some of the biggest male polar bears in the park like to hang out.

In 2022, six of the cameras were broken by polar bears. Turner knows this because the raccoons who did this were caught on camera.

The cameras have also taken pictures of grizzly bears, Arctic foxes, 25 types of birds, and scientists who walked in front of the motion sensors. But the caribou were in almost all of the 68,000 pictures that were taken during the first year of the project.

“One interesting pattern we can sort of see is that not many people use the park or move around much in the winter. “In May and June, you see a lot of different species, but in the winter, you only see wolves and foxes,” Turner said.

The cameras also get close-ups of animals that look at them and views of the backs of the animals.

Turner joked, “We definitely get a lot of butt pictures, and a lot of caribou walking away from the camera.”

Researchers also want to use the cameras to prove what has been known for years: that caribou prefer to migrate along dry beach ridges instead of slogging through wet fens.

Turner said, “We’re trying to use these cameras to find out when they’re in different places and what habitat they’re using. We’re also hoping to learn more about their predators and what they do in the environment.”

Ryan Brook, a wildlife ecologist at the University of Saskatchewan, thinks it’s interesting to see where timber wolves are in relation to the caribou they eat.

“They nest mostly in the wooded areas at the south end of the park, but they will go further north to where the caribou are every day or for longer periods of time,” he said at Nester One.

Riley Bartel, the conservation coordinator for the Manitoba Métis Federation, said that his group hopes to use the data from the cameras to help create an Indigenous protected area for the Cape Churchill caribou herd southwest of Wapusk.

For this to happen, the provinces would have to agree, but Parks Canada is already on board.

“Their summer grounds are protected, but if their winter grounds could also be protected, that would help save this species even more,” Bartel said at Nester One.

Turner wants to show that protecting the caribou’s habitat is directly linked to the health of the caribou population. This seems like an obvious connection, but science hasn’t shown it yet.

“I think that would be a big plus for any new parks that might be protected,” he said.