It hurt that I couldn’t call myself an architect in Canada after working as one for 9 years in the Middle East

In this First Person column, Komaldeep Makkar, who used to live in Canada but now lives in Dubai, talks about his life there. See for more information on CBC’s First Person stories.the FAQ.

I grew up in Punjab, which is a state in India. It seemed like almost every street in my state had billboards advertising a better life, more jobs, and higher pay in Canada. I knew a lot of families whose younger children were taking English classes in preparation for tests to move to Canada. I will never forget the pride in those parents’ eyes when they told me that their son or daughter had moved to Canada. It made me think that Canada had a lot to offer and could be my home one day.

I went to school in India and got a bachelor’s degree in architecture and a master’s degree in urban planning. As an architect, my job took me to New Delhi and then Dubai, where I worked for international companies. In Dubai, I had a good work-life balance and made a salary that I probably never would have made in India. But if you are an expat living in Dubai, there is no easy way to become a citizen. So, in 2017, I applied to Canada’s Express Entry program to further my career goals and find a place to live permanently. During the application process, I got married to an architect. I got my permanent residency visa in early 2020. My husband and I were happy to finally make the move we had heard and read so much about.

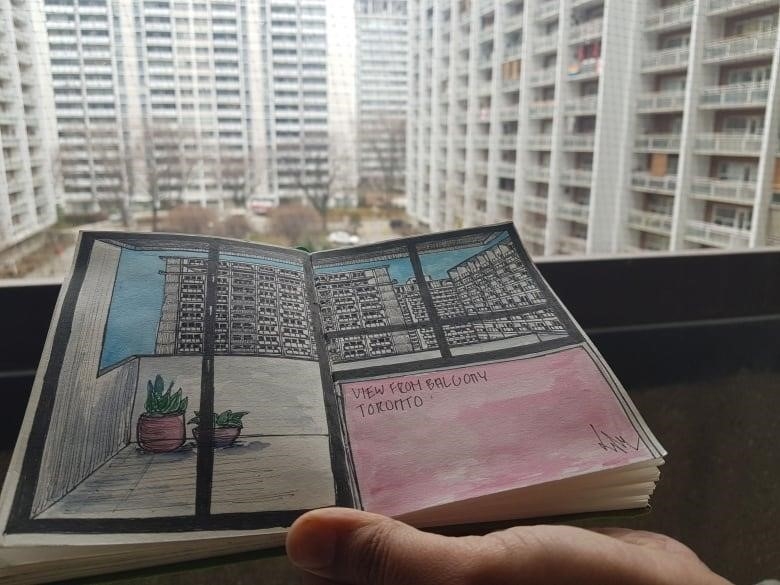

When we got to Toronto in January 2021, it was the first time we saw snow. I loved the clean air and the sounds of nature, which were so different from those in India. But soon, the cold calls that went nowhere made our winter even colder. After looking for a job for a few months, I realized that my education and nine years of experience as an architect in the Middle East didn’t matter.

When we moved to Toronto, we joined government-funded programs for newcomers to learn how to use our skills and experience in the Canadian market. Multiple employment counselors told me to take off my master’s degree from my resume, even though it gave me more points in the express entry program. They also kept telling me to take some years off my resume or leave off some of my more well-known projects so that I wouldn’t look too qualified for the jobs that were open.

In Canada, you need a license to be an architect, which is another way of saying that I could no longer call myself an architect. I could only say that I was an architect with training from around the world. To add to our confusion, the federal government is in charge of immigration, and we did well on the points system because of our qualifications. However, the province is in charge of licensing requirements, and they didn’t recognize our degrees. If I wanted to call myself an architect, I would have to enroll in an expensive Canadian master’s program and repeat the degree I already had or work my way up the corporate ladder by taking internships at the bottom. This is what counselors and other immigrants who had made it told me to do. I felt very insulted and disheartened..

Most of the second interviews I went to were for unpaid or co-op work. I got a few job offers as an architectural technician, but none of them paid more than $15 an hour. I was confused. I had spent many years and a lot of money trying to get permanent residency in Canada. But instead of getting a job in the field I had studied and worked so hard for, I was spending my savings every day just to keep up with the cost of living in Toronto.

My husband and I started to lose hope in the Canadian dream when we saw how things really were. Both of us had worked on big projects in places like the Gulf states, Africa, and India. And here we were, new to the country, telling companies why we didn’t have this “Canadian experience” that seemed so special.

We thought about what to do. To stay would have meant spending a lot of money on more schooling in the hopes of getting a job as an architect in Canada, while also putting off our plans to save for retirement or buy a house. Our many years of schooling and working abroad would have been for nothing. We decided to leave because we didn’t want to live in a country with systemic barriers that make it hard for immigrants to do well in their jobs. I care too much about myself to stay.

I don’t understand how the Canadian government can say it plans to welcome 500,000 immigrantsA year to make up for the lack of workers in the country, but that doesn’t seem to stop qualified professionals from being treated badly. We’ll keep hearing about foreign-trained doctors who become Uber drivers and teachers who can only find work as janitors until that gap between immigration policy and hiring loopholes is closed.

I also completely understand why so many immigrants like us choose to stay: to prove that the dream they have been told about their whole lives is real. A lot of them are even from where I live. I never thought I would throw in the towel until I looked at my bank statements.

We live in Dubai and have good jobs that let us call ourselves architects with pride. We have a good standard of living that our parents can be proud of. We have no plans to return.

Do you have a compelling story about yourself that can help others understand or learn something? We want to know what you think. Here’s More information about how to sell to us.