A group from Manitoba wants to meet with 400 applicants who have already been screened in the Philippines

When Nikka Reyes moved from the Philippines to Winnipeg in 2015, she hoped that her job as a registered hemodialysis nurse would lead to a bright future.

Eight years later, she’s a Canadian citizen, but the 34-year-old lives and works in Tennessee because she couldn’t get accredited in Manitoba.

She also doesn’t understand why provincial governments send recruiters to the Philippines instead of using those funds to help nurses who were trained in other countries but are already living in Canada.

In a recent interview, she asked, “Why are we wasting their skills and abilities when we need them right away?”

Reyes is not the only nurse who went to school abroad and has these worries. CBC News talked to a number of people in Canada who had similar stories.

One of them, a hemodialysis nurse who worked for an insurance company in the United States for six years, said she started her RN application in 2019 after moving to Winnipeg.

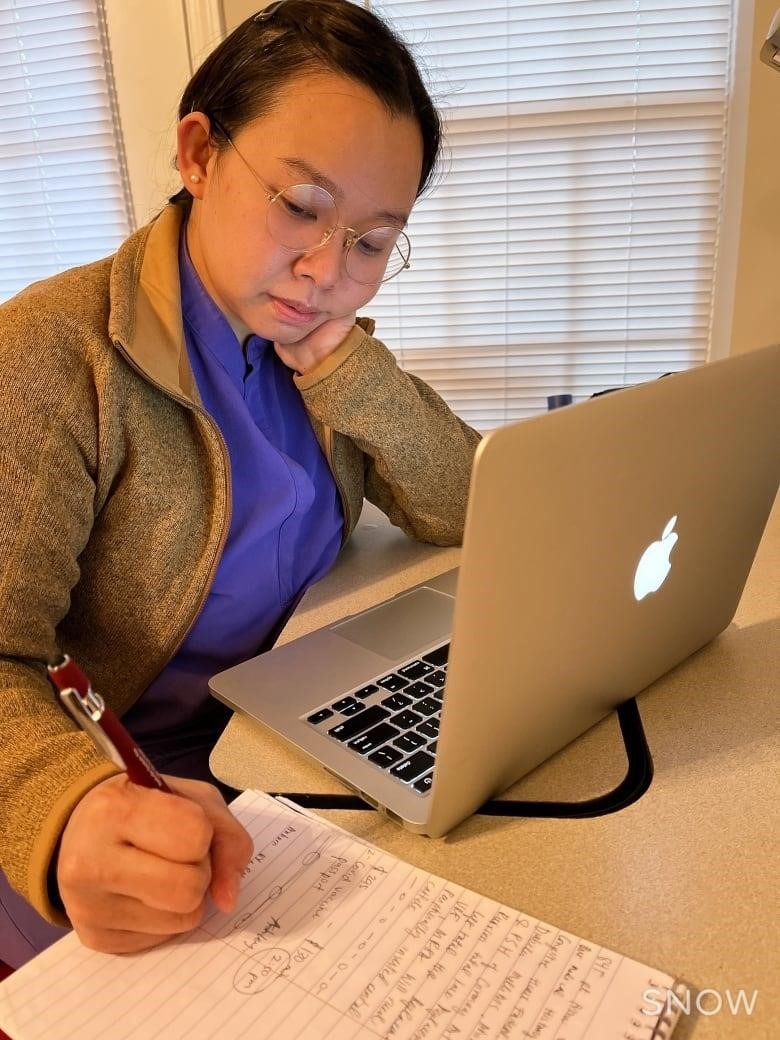

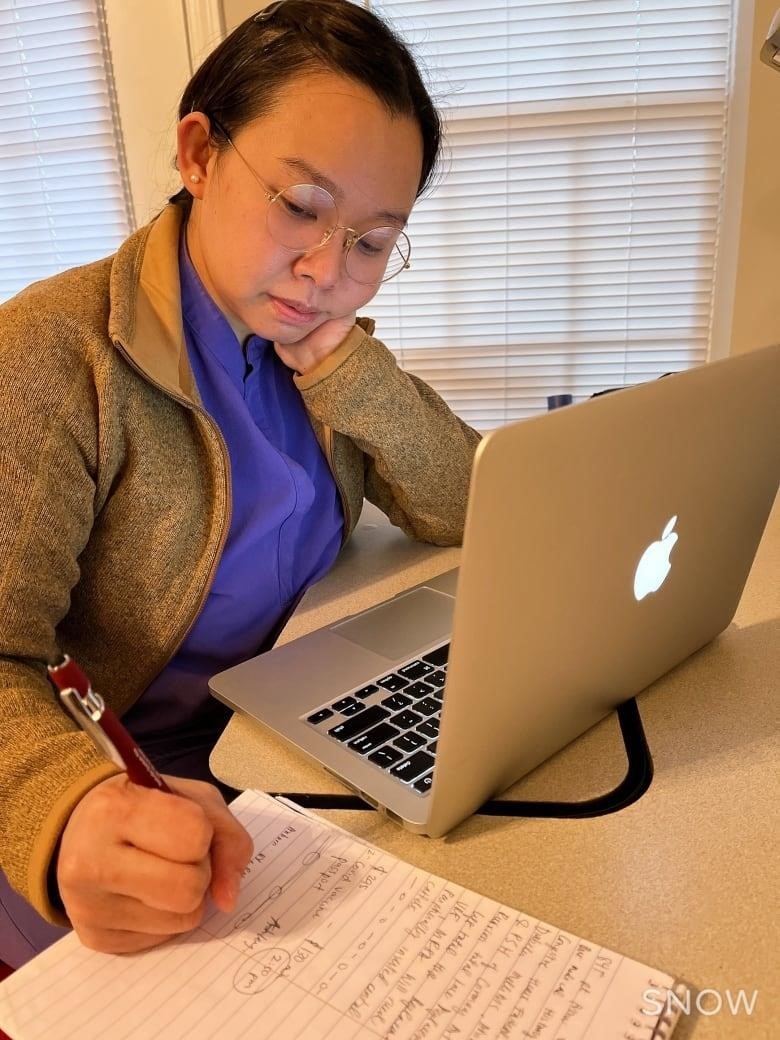

The woman was told to take a skills-bridging course at a local community college, but she says she can’t study full-time because she is a single mother and works as an aide in a Winnipeg personal care home. She is afraid for her job, so CBC won’t say who she is.

She has taken some of the required courses online, which each cost $1,500, but she has also used her vacation time to return to the Philippines to upgrade. Still, she failed the part of the English language test that was about listening. She thinks that competency tests alone have cost her around $2,000.

The woman was upset that the government of Manitoba was sending a recruiting mission to the Philippines. She said she felt forgotten and left out. She wants the government to give more jobs to nurses who are already in the country.

About a third of health workers in Canada have degrees from outside the country.26% of doctors and 9% of nurses don’t like what they do.Over the past year, provinces have put incentives in place to get more people to move there.targeted immigration streams. But up to 47 per centSome of those nurses and doctors don’t work in the jobs they were trained for.

Some people find that their credentials and language skillsDon’t meet Canada’s requirementsOthers can’t start working in their field for months or even years because getting a license or registering can take a long time and cost a lot of money.

The federal government’s most recent budgetincluded money to help thousands of health workers who got their education abroad get their foreign credentials accepted.

Looking elsewher

But provincial governments still look for nurses and other health care workers in other places.

Right now, a group of people from Manitoba are in the Philippines.

Jon Reyes, Manitoba’s minister of labor and immigration, said in an interview before the delegation left that he hoped a renewed memorandum of understanding with the Philippines government would “ensure the well-being of both Manitobans who use these services and Filipinos who come here.”

A person who works for the Philippines Department of Health is worried about the number of health care workers who are leaving the country. Officer-in-charge Maria Rosario Vergeire told reporters last fall that the United States is short 106,000 nurses in both public and private facilities and hospitals.

-

When Canada tries to “poach” nurses from other countries, it makes people in developing countries worry about shortages.

- Vitalité will hire doctors and nurses from West African countries that have even bigger shortages.

She said that one reason for the shortage is that nurses are moving to other countries to find jobs with better pay and conditions.

As a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Philippines put a cap on the number of nurses who could leave the country to work each year. This cap was set for 2020. The limit is now being lowered gradually, but Vergeire said she wants to keep it.

Reyes, who is the minister of labor and immigration in Manitoba, is one of the people who agree that finding enough people to work in health care is a worldwide problem right now.

Reyes said, “I know it’s a worry for the Philippines.” “There needs to be equal treatment between Manitoba and the Philippines if we want to get more nurses here.”

The Philippines government told Manitoba Health Minister Audrey Gordon, who is not on the recruiting trip, that “they actually have a limit on how many people can leave their country, and we’re not in any way going against that.”

“We are very aware of how important it is for these countries to keep their services running,” she said.

Reyes and Gordon both said that the Manitoba government is working with regulatory bodies to make it easier and faster for nurses with international degrees to get their licenses.

Gordon said, “I’m telling the people who have left to come home and come back to Manitoba because there are a lot of opportunities here.” “If you live in Manitoba, don’t leave yet, because things are getting better.”

Offering immigration suppor

Twenty clinicians and recruiters will be in Manila, Iloilo, and Cebu for five days to talk to 400 people who have already been screened. They are looking for health care aides and nurses with at least two years of experience in a hospital or long-term care setting.

They will pay for your trip to Manitoba, put you up for up to three months, pay your license and registration fees, and help you through the immigration process. Those who come will also be given a mentor to help them during their first few weeks on the job.

“Our employers are very invested and excited,” said Monika Warren, who is in charge of nursing at Shared Health, the government agency that runs the health care system in Manitoba. She is one of 20 clinical leaders and recruiters from different health districts and hospitals who are doing interviews in the Philippines this week. She is in charge of making sure there are enough nurses in the province.

“They really see this as a glimmer of hope that will help us get through what have been very hard times.” So, I would say that we hope that some of those people will start to come to Canada in the coming months so that we can get to work.

Watch Monika Warren talk about what she wants and what Manitoba needs:

Warren thinks that there are between 1,500 and 2,000 open nursing jobs in Manitoba and that most of them are in rural areas.

“Every day, I feel the weight of that.” “It’s an absolute must.”

Even though there are four people applying for each nursing education spot in Manitoba, Warren said, “We need some time to get through this tough time.” “I think this recruitment from the Philippines will really help us bridge the gap until we can start training more nurses in the province.”

Working with the colleg

Warren said she is working with the College of Registered Nurses of Manitoba to “make sure that path is as quick as possible and the door is as wide open for them as possible” for international nurses who want to get provincial accreditation.

“I need them, and I want them in the workplace just as much as I want the nurses we’re hiring from the Philippines,” she said, adding that the longer someone hasn’t worked, the more training they will need.

Ken Borce is going on the trip as a representative of what can be done in Manitoba. He went to school abroad and became a nurse. In 2008, he moved from Manila to Winnipeg and worked in acute care. Since then, he has worked his way up to become the head of clinical operations at Cancercare Manitoba.

Borce said that he will talk about Manitoba’s rich Filipino culture and the many chances for career growth that he sees there.

“I really believe that Manitoba is the best place for them to start over with their dreams. “I’m one of many people who have done well in life, and I’d like to tell my story to give hope and optimism to the Filipinos we will meet on this mission.”

Watch as Ken Borce tells Filipino nurses why they should hire him:

But there is a lot of competition around the world and in Canada for these nurses.

Alberta has made a deal with the government of the Philippines to hire nurses. It also recently announced a $15 million plan to train and help more nurses obtain international degrees. The plan includes $7.8 million in student bursaries and 600 new seats in programs that help nurses improve their skills and qualifications.

In December, the government of Saskatchewan went to the Philippines to recruit health care workers. More than 1,200 Filipino health care workers attended the 10 workshops and information sessions. At the end of the week, 128 registered nurses and one continuing care assistant were given conditional job offers.

A spokesperson for the provincial Health Department said that a group from New Brunswick is also planning to make a similar trip soon.

“The process is just impossible to understand.

Some nurses who went to school outside of Canada and moved to Canada are shaking their heads as they watch these recruiting efforts.

“The process is just impossible to understand.” “We’re all in the dark,” Nikka Reyes said.

After she moved to Canada in 2015, she opened a file with the National Nursing Assessment Service (NNAS), a Canadian non-profit that makes it easy for nurses who were educated outside of Canada to send in their documents.

-

The Philippines recruitment trip is “great news,” says the head of the nursing school in Manitoba.

-

Manitoba should focus on registering nurses who have been trained abroad and are already in the province.

Reyes applied for jobs as both a licensed practical nurse and a registered nurse in Manitoba and Ontario. She took classes and took tests to see how well she could do these jobs. She had to pay $1,400 for the applications.

But she failed her Canadian English Language Benchmark Assessment for Nurses (CELBAN) test three times because she couldn’t understand what was being said. Before she can try again, she has to wait two more years.

Canada just lowered the benchmark scores for the listening and writing tests last year, so Reyes and several other nurses with international degrees who CBC News has talked to would have passed.

“I did everything I could to get a license there, but it didn’t really work out.” First step: say “no.” Second step: negative. “It took two to three years, and I still can’t see the light at the end of the tunnel,” she told me.

“It came to a point where I told myself, ‘Maybe this is not for me.'”

“It came to a point where I told myself, ‘Maybe this is not for me.'”

“It came to a point where I told myself, ‘Maybe this is not for me.'”

Reyes got her license to work as a nurse in the United States on her first try at a test.

She has worked near Nashville for almost three years and wants her contract to be extended.

“I’m not getting any younger… “So that’s what made me decide.”

Reyes is worried about Canada’s health care system because there aren’t enough nurses, and that’s only going to get worse. She says that wait times for tests and procedures will keep getting longer because there aren’t as many trained staff.

Her advice to nurses who went to school outside of Canada and are now working hard to get licensed in Canada?

“Don’t close your doors.” Open your research to the public and look for other ways you can use your nursing skills. “I know it will be hard, but a lot of countries need nurses,” she said.

“Canada is a good country, but it is not a friendly country for people who work as nurses.”