Because of my race, people have treated me badly when they didn’t have to

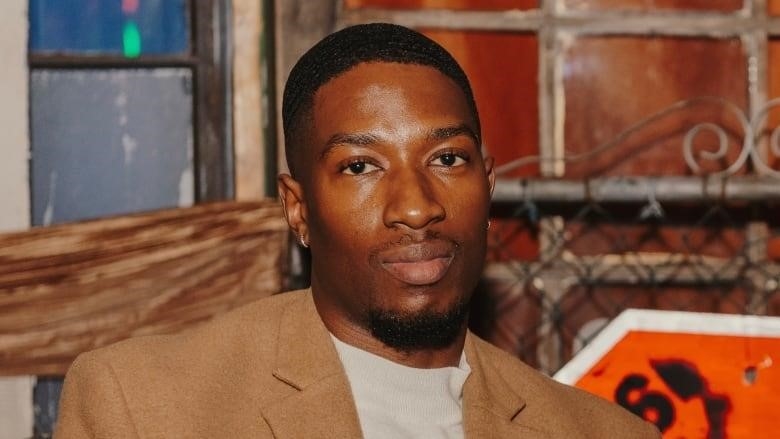

Shaquille Morgan is a policy consultant and writer. In this first-person column, she talks about her own life. See First Person Stories for more information.the FAQ.

When I was growing up in Mississauga, Ont., my mother or grandmother never had a specific “talk” with me about how I, as a black boy, should act around the police.

I now recognize why.

There’s just too much to talk about for it to be a single lesson, and my mom is afraid of these talks because she knows there will be a time when the police will target her child because of their race and she won’t be there to protect them.

I learned bits and pieces about the police. When my mother was in the wrong place at the wrong time, she was harassed, pinned against the wall, and questioned. This taught me a lesson. I learned this as I walked down the street with my mother and brother and saw the police randomly stop, search, and sometimes scare black boys and men because of how they were dressed, with XL T-shirts, baggy jeans, and heavy chains that swung as they walked.

The world and the police seemed to think that the way they dressed and acted was a problem, so they were seen as bad. But I saw them asflyand I liked that if nothing else. When my mom saw this, she would scold us out of fear and worry.

“Do you see?” I never want to see you on the street when you’re that old. “The library is the only place I want to find you.”

I never asked her why she was telling us these things. Even when I was young, I knew that black people were treated differently, but I didn’t understand why I had to act differently because of that. When I was 15, I found out the answer to this question.

I was almost done with my lunch break. After I played basketball, I went to the plaza next to my school to get something to eat. I ran over, my Jansport backpack full of books and binders that bounced as my feet hit the ground in a steady rhythm. I heard someone yell from far away.

“Stop! Don’t let me come and get you!

I didn’t bother turning around because I thought the order was for someone else. I hadn’t broken any rules.

I heard the voice say again, “Don’t make me say it again!” I was still running when I turned around and saw, to my surprise, a police officer following me.

“Me? But I didn’t do anything. As my jog came to a stop, I said, “I don’t know what’s going on.”

I didn’t get it. I remember feeling like my stomach was empty. As a child, I felt the same pit when I saw the police stop my mom because of her race.

He got right up close to me, made me sit on the curb with my arms behind my back, and took out a small notepad. Before he asked me for my student card, he said, “I’ve seen you around here in your blue shirt making trouble.”

I didn’t say anything because I was confused and knew I wasn’t the person he thought I was. I can only assume that he was looking for a “troublemaker” and that I was the one he saw because I was a young black man running.

He then asked me about a fight that had happened at the plaza. I told him there wasn’t a fight. But it didn’t seem like he cared what I said. He asked me questions until he was satisfied, then he closed his notebook and told me I couldn’t go to the plaza for three months.

“We’ll have trouble if I see you around here before then,” he said as he gave me back my card.

I quickly grabbed my card and ran back to school, looking nervously over my shoulder to see if he was watching. I thought about telling my mom, but I didn’t. I didn’t tell anyone. If I had asked, they might have told me that he couldn’t do that. Still, I can’t help but think it wouldn’t have made a difference because I haven’t seen the police held accountable for their actions very often.

From this interaction, I developed a deep distrust, anxiety, and even some fear of the police. Black people don’t call the police because they are afraid of the same thing. Since then, it’s been hard for me to forget how I felt. When I think about this event, I know I wasn’t hurt. I wasn’t put in jail. But when I look at how things are now, with the death of Tyre Nichols and the many times black people have been hurt by police, I’m reminded of what happened in the past.could’ve been.

I don’t know how many times the police have tried to catch me since then. I can’t also say that it’sthat often.

I know that I’m lucky to be able to say this because it’s been much worse for other people. I can tell you, though, that I’ve been followed home at random, asked for my ID because I “looked suspicious,” and asked if my real name was Jerome or Tyrell. I no longer ask myself.if Interactions like these will happen. I ask myself:when. Even though I know I and my community deserve better and that people are working to change this, I’ve had to accept it as a fact.

Check out Being Black in Canada, a CBC project that Black Canadians can be proud of, for more stories about the experiences of Black Canadians, from racism against Black people to stories of success in the Black community. You can find more stories to read here.

Have you had an experience like the one in this first-person column? We want to know what you think. Send us an email at [email protected].