The move comes as Ejaz Choudry’s family sues Peel Regional Police for $22M in civil court

West of Toronto, a police agency is trying to keep the names of the officers involved in the death of Ejaz Choudry from being made public. Choudry was a father of four with schizophrenia who was shot and killed by police, who said they had to act because they were afraid for their own safety.

Peel Regional Police say that releasing the names of the five officers involved in the death of the 62-year-old in June 2020 would put them and their families in danger. This includes the officer who shot two bullets into Choudry’s chest after his family called a non-emergency line when he was in trouble.

CBC News plans to fight against the request for a publication ban.

In May, lawyers for the force told the Ontario Superior Court of Justice that “the officers fear for their own safety and mental health, as well as that of their families.”

The police motion says that one officer involved in the shooting said he is afraid to go out in public with his family because he has been threatened and scared on social media and at protests.

Choudry’s family members say that the plan to ban the book stinks of irony.

Nemrah Ahmad, Choudry’s daughter, said, “Even though they didn’t care about my dad’s safety and well-being when he was having a mental health crisis, these officers have asked the courts to respect and put theirs first.”

Ahmad said, “It’s just an excuse to keep their names from the public.” “Everyone needs to be honest and take responsibility.”

The hearing is set for April of next year. Lawyers for the family, Simon Bieber and Chris Grisdale, refused to say anything.

A call about mental health turned into a “tactical operation”: a lawsui

The motion comes as Choudry’s family gets ready for a long court battle. They had hoped that the officers would be charged with a crime, but Ontario’s police watchdog decided not to do that.

In April 2021, Ontario’s Special Investigations Unit said the officers did the right thing, saying that the decision to open fire was “reasonable, necessary, and proportional to the threat posed by Mr. Choudry.”

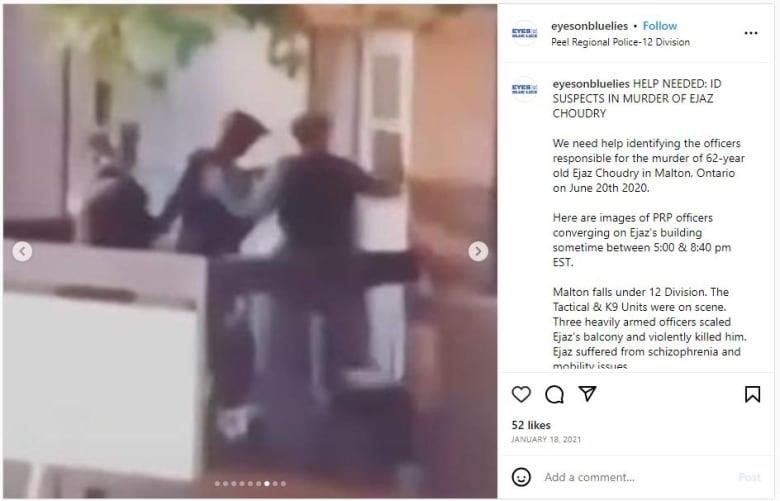

WATCH | A bystander’s video shows tactical police officers in front of Choudry’s house:

Last June, Choudry’s family filed a $22 million civil suit against the Peel Regional Police Services Board, Chief Nishan Duraiappah, and five individual officers for what they say was a “reckless” response to a mental health distress call that led to Choudry’s death.

Police say that they were being threatened by a man with a gun, and that non-lethal methods did not work to stop him.

The civil suit, which has not been reported on until now, says that the officers’ actions violated Choudry’s right to life under the Charter, amounted to cruel and unusual punishment, and went against his right to equality as a racialized person in crisis.

It also says that the way Choudry was treated by the officers “fell well below” what should have been done.

The lawsuit says, “They carelessly let a simple mental health call get out of hand and turn into a high-risk tactical operation.” It also says that the police “used deadly force without reason.”

“The operation was done on an old, frail, racially mixed man who did not speak English well and had mental health problems that were not life-threatening.”

In court, none of the claims have been shown to be true.

Shot within 11 second

According to the claim, Choudry’s family called Peel paramedics at 5:30 p.m. on June 20, 2020, because they were worried that he wasn’t taking his medication for schizophrenia. They said that Choudry looked confused. It wasn’t the first time they’d seen something like this, and in the past, they’d dealt with similar situations “without incident.”

But Choudry would die that day instead of getting help from a doctor.

Choudry’s daughter told the dispatcher that he was carrying a small pocket knife but wasn’t dangerous. When the paramedics called for help, the police told Choudry’s family to get out of the house.

When the police showed up, they spoke English and asked to see Choudry’s knife. His daughter had to translate for him. Choudry then pulled a 20-centimeter kitchen knife out from under the mat he was sitting on and told the police to leave.

According to the lawsuit, Choudry said that he “would not leave his home because he was afraid that the officers would shoot him.” The family’s civil claim says that when a Punjabi-speaking officer arrived later, Choudry told him he didn’t want to hurt himself.

Still, instead of waiting for a mobile crisis unit, officers gathered in front of Choudry’s door and on his balcony with plans to arrest him under the Mental Health Act. Around 8 p.m., Choudry stopped talking to police. After that, the suit said, police broke into his house and yelled at him in English.

Within 11 seconds of breaking down Choudry’s door, police Tasered him, shot him with three rubber bullets, and put two bullets into his chest, killing him.

Later, the police said that there was no mobile crisis response unit available at the time Choudry’s house was visited. His family thinks that Choudry might still be alive if the police had waited for the crisis team.

In a statement of defense, police lawyers denied the accusations and said they broke into Choudry’s apartment because they were “immediately concerned for his safety” because of his family’s medical history, the fact that he was in a crisis and had two knives, and the fact that they hadn’t heard from Choudry in a long time.

The statement says that when police entered the house, Choudry came at them with the knife “in a threatening way,” and non-lethal ways to stop him from moving forward did not work.

It also says that any losses or damages the family suffered were because of “their own negligence.” It says that they didn’t make sure Choudry took his medicine or got medical help when he needed it, and that Choudry should have known that having a kitchen knife would make the police come.

In the statement, the police also say that they thought Choudry knew English and that Chief Durappiah shouldn’t be named in the lawsuit.

In October 2022, that defense was filed.

Officer who shot Choudry said, “I’m afraid.

In a motion filed on May 19, 2023, lawyers for the police say that after Choudry’s death, officers faced multiple threats, including posts on social media asking for their names to be made public, “vitriolic” comments made at protests, and a banner on a major highway calling Peel police “murderers.”

The motion says that the threats came from a community group called the Malton People’s Movement, which formed after a series of deaths involving Peel police, an Instagram account called Eyes on Blue Lies, and individuals like a YouTuber who threatened to reveal the home address of at least one officer.

Choudry was one of four people of color with mental illness who died at the hands of Peel police in just a few months, his daughter says. This happened around the same time that George Floyd was killed by police in the U.S. Among these deaths wereClive Mensah in November 2019, Jamal Francique in January 2020 and D’Andre Campbell in April 2020.

The motion says that three people from the Malton group were charged with mischief after throwing red liquid on the walls of a police division during a protest after Choudry’s death. The motion says that at a protest in July 2020, a relative of a man killed by Peel police in 2014 said, “Why can they just shoot us like this?” What if we start to arm ourselves and shoot back?”

Choudry’s daughter said that no one in Choudry’s immediate family was involved in the protests, and no one in Choudry’s immediate or extended family was ever charged with anything related to the protests.

Affidavits from the officers involved, in which they say what they were afraid of in their own words, are also part of the motion. One of them is John Doe Officer 1, who is known to be the officer who shot at Choudry.

“I’m not making things up when I say this is scary. Time hasn’t helped, and I’m afraid of how much worse things could get if my name gets out,” the officer says, adding that he has added more locks and video surveillance to his home and taught his family to be aware of their surroundings.

The officer also says that going out with family “has become more of a chore than a pleasure because of the steps we take to protect ourselves” and that he worries about his wife, her business, and their children.

Family says it’shouldn’t have to fight’ for opennes

In a report that was part of the motion, a threat assessor who worked for Peel police said that naming the officers involved in Choudry’s death would “increase the risk of violence toward them and should be avoided.”

The assessor says that her pay “is not tied” to what she finds. She says that since the summer of 2021, there have been “no identifiable threats or concerning communications sent to the police.”

When asked about how police connected Choudry’s death to threats made against them, his daughter told CBC News, “I have a right to know who killed my father, and it’s nonsense for them to use things that no one can control as proof to hide their identities.”

“I shouldn’t have to work so hard to find out the names of the people who made our lives worse.”