“These rocks… tell us a lot about the history of our universe and how it came to be.

A piece of the upcoming space mission that will study where asteroids came from comes from Manitoba.

In June, a satellite made by engineering students at the University of Manitoba will be sent to the International Space Station.

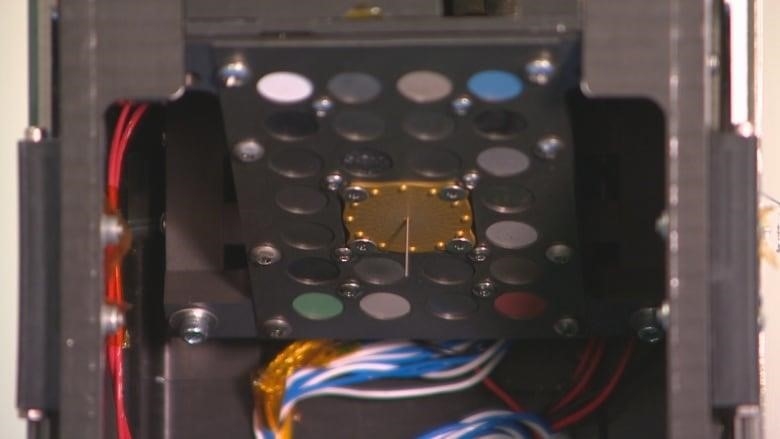

The satellite, which is about the size of three stacked Rubik’s cubes and is called Iris, was made to study how space conditions affect the composition of asteroids and the moon. This will help scientists on Earth better understand these effects when they study meteorites.

Philip Ferguson, an associate professor in the U of M’s department of mechanical engineering and the founder of its Space Technology and Advanced Research Laboratory, or STARLab, said, “This will be the first satellite ever built by University of Manitoba students that is in space.”

“Even though we have built satellites at the University of Manitoba before, we have never sent one into space. Even just thinking about it gives me chills. We’re happy.”

The project was led by STARLab students, who worked with Toronto’s York University, Manitoba’s Interlake School Division, and Magellan Aerospace.

Iris is Manitoba’s contribution to the Canadian Space Agency’s CubeSat project. It was designed and built over the course of about two years and cost about $20,000 to do so.

Ferguson said, “It sounds like a lot of money, and it is, but compared to the hundreds of millions of dollars it costs to make a big satellite, this is nothing.”

“This is made with the same kinds of parts that you’d find in a cellphone.”

Ali Barari, who just graduated from the University of Michigan and worked as a payload system engineer for Iris, thinks of Iris like a child.

“We thought of it and made it from scratch. This was made by us. Everything came together, “he said. “It feels like a lot of fun… like a dad to a child.”

Ferguson said that was part of the project’s goal: to make reliable space missions with easy-to-find commercial parts.

For example, Iris’s antenna is a piece of a tape measure from a hardware store, with the numbers still on it.

“We’re trying to do this with everyday parts you can buy at any store,” Ferguson said. “But we’re making them so they can survive a trip to space.”

“It’s no longer just for companies with a lot of money.”

Junior high school students in the Interlake School Division’s space club learned how to figure out the sun’s angle and made a sundial that will help Ferguson’s team figure out which way the sun is facing by looking at the shadows.

CubeSat started in 2018 and allows students at post-secondary schools in every province and territory to take part in a real space mission by designing, building, and launching their own small satellites.

Then, student teams run their satellites and send them on missions.

Some CubeSats have already been sent to the International Space Station and set up there. Ferguson said that the space agency had planned for the launches to happen in three groups, with the first two beginning in 2022 and 2023.

“Every satellite built in Canada was made for a different reason. Ours is to look at rocks in space. We want to know what happens to rocks in space ” Ferguson said.

“These rocks are very interesting because they can tell us a lot about the history of the universe and how it came to be.”

Instead of collecting space rocks, Iris will take a few tiny pieces back to the big space where they came from.

“We think that some of them might change how they reflect light, some might change color over time, and some might not change at all. We don’t know — it’s not often that people put rocks back into space,” Ferguson said.

Inside Iris, where the rocks are held in place, there are cameras that will take pictures and send them to Ferguson’s team.

On the roof of the university’s engineering and information technology complex is a communications station with a big antenna. “We’ll be able to talk to it the first time it goes overhead,” Ferguson said.

“The satellite is programmed to open up its antennae and open up its solar ray and then it’s going to phone home … when it comes over top of Winnipeg.”

He expects it will take the astronauts a couple of months to get settled in and unpack all of the cargo they take up to the space station. Iris will likely get released sometime around July or August.

Ferguson said that it will be a little scary until the first signal comes in.

“You just keep hoping and hoping that you’ll get that signal, but I think it’ll be a big deal when we do.”

Ferguson hopes that Iris will do its job for two to three years, but he also said that it will slowly fall out of orbit until it crashes into the Earth’s atmosphere and burns up.