From the n xaxaitkw to the Shuswaggi, people continue to see and talk about what they don’t know

If you go to a popular lake in British Columbia, you’re likely to find a beach, some boats, and a story about an unknown creature that lives under the water.

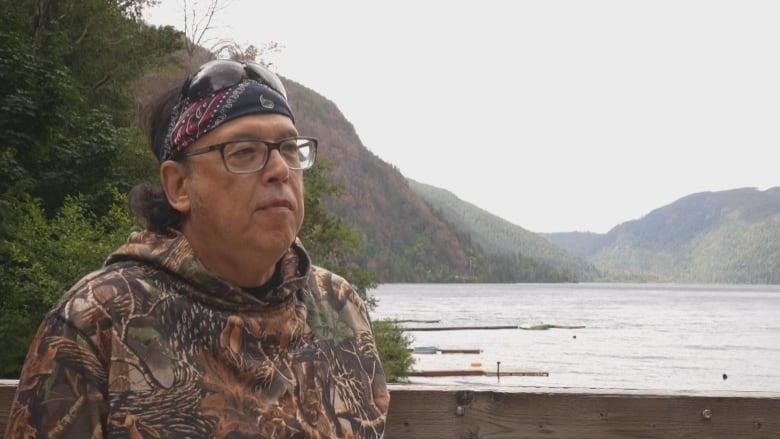

“There is a sense of mystery when we talk about water. Westbank First Nation Coun. Jordan Coble thinks it’s because we don’t fully understand the power and potential of water on its own.

He is one of the people in his community who are in charge of telling the story of the n xaxaitkw, also called Ogopogo, a lake monster that looks like a snake and is probably British Columbia’s best-known lake monster.

“People are interested. “It makes people want to be more aware,” said Coble.

There is also the story of the Shuswaggi in Shuswap Lake, which is similar to the n xaxaitkw in Okanagan Lake. A sign at Sproat Lake says that some of the ancient petroglyphs carved into the rock faces could be sea serpents.

Around Harrison Lake, a small business has long been based on the legend of the Sasquatch.

WATCH | A look at the history of the Indigenous people and the geology of Sproat Lake:

So why do lakes in this province seem to inspire stories more than rivers, oceans, mountains, or forests?

“We’ve always had imaginative minds.

John Kirk has a theory. He is the head of the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club.

“Throughout history, people have always had a lot of ideas about places they couldn’t go to, like the deepest parts of a lake,” he said.

Kirk has been studying lake cryptids, which are creatures that people have seen but science has never been able to prove exist, since 1987. He says that B.C. has a lot of deep lakes surrounded by forests, which is a good place for all kinds of animals to live, but people might only get a glimpse of what it’s really like.

“You might think it’s a sturgeon, a big brown or rainbow trout, or even a group of otters swimming in line. You start with the ones that make sense,” he said.

“What are you left with when you get rid of them all? The mystery is all that’s left. And that mystery is what has kept us going all this time.”

Kirk is very interested in the subject, but he warns people not to think there are a lot of undiscovered creatures out there. He said that people have seen unknown animals in 42 different B.C. lakes, but further research into these claims hasn’t shown anything conclusive.

“It’s very hard to find proof because they’re the most elusive animals that have ever lived,” he said.

“This won’t stop until we figure out what’s out there, and I’ll probably keep doing it for the rest of my life.”

“It’s a rule we have to follow.

Coble wants people to remember that the story of the n xaxaitkw is about the creature revealing itself as a spirit to remind people that they need to protect the lake. This is true whether lake lore becomes part of the paranormal or is just used for tourism.

“It’s not just a person or a thing… “It’s a law that we have to follow, and it just means that we have to be aware of our responsibilities to protect water for everyone, both people and animals,” he said.

“We have to live in a way that is fair to everyone, and we have to do our best to protect the good things in the water and keep the bad things out.”

When the City of Vernon gave the Sylix Nation the rights to the name “Ogopogo” two years ago, the public was forced to talk about who has power over lake stories and who owns them.

Coble thinks it’s a chance for Indigenous people to take back control of how these stories are told and put the values of their communities at the center.

At the same time, he knows that as long as there are lakes, people will always see things that can’t be fully explained, and their imaginations will always run wild.

“There is definitely some sensationalism in modern media… “At the same time, people have been telling stories for hundreds of years about big animals in and out of the water,” he said.

“Everyone has the right to tell stories, and we have to be creative and critical about how we understand them… But sometimes it’s nice to just listen to a good old-fashioned tall tale and take a break.”