His hospital surveys about long COVID got us talking about our emotional health

This first-person article is about the life of Toronto resident Joel Rodriguez. For more information about CBC’s first-person stories, visitplease see the FAQ.

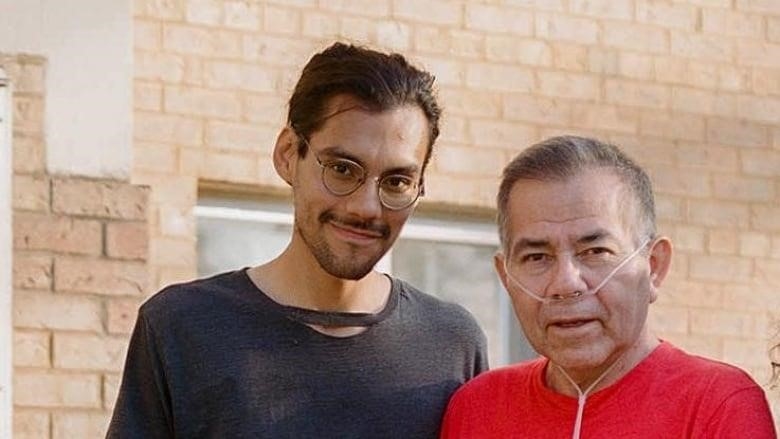

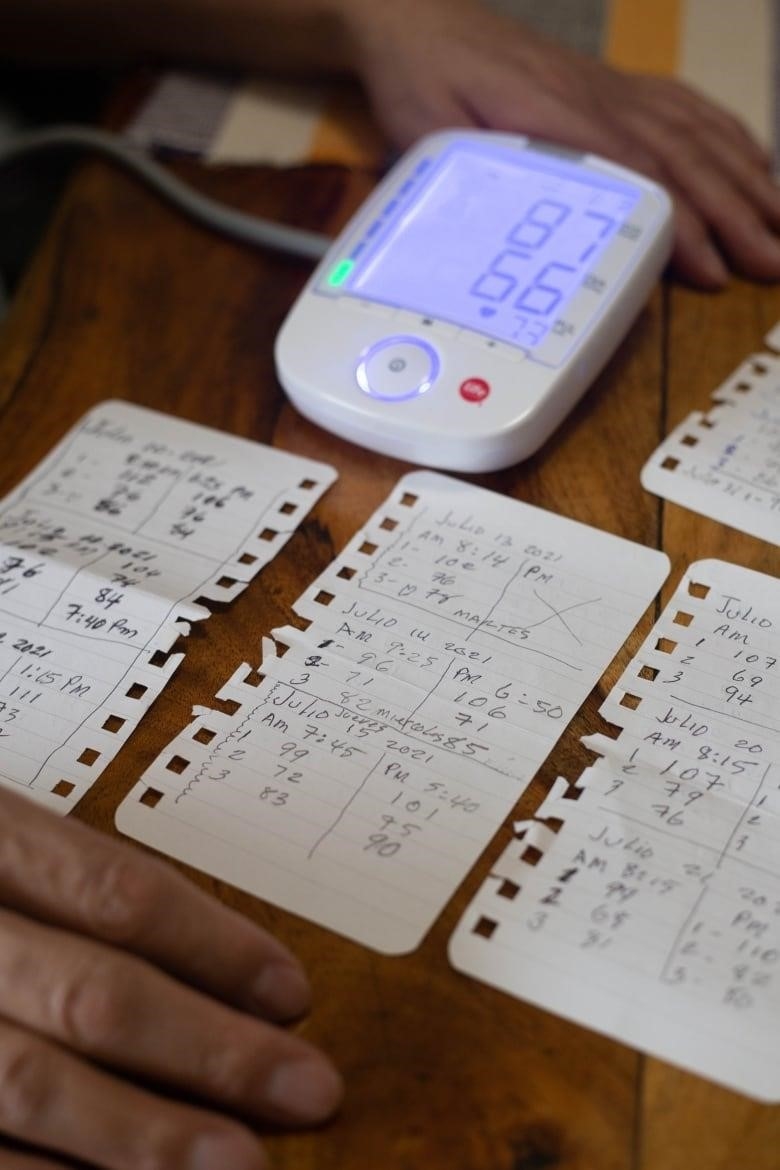

My dad checks how much oxygen is in his blood while we both sit at the kitchen table in the afternoon sun. My dad waits with bated breath as the machine beeps and spits out a reading of 97. He looks up and smiles at me. The reading is good news, and the fact that my dad no longer needs oxygen when he’s resting is a reminder of how much he’s improved.

But reading isn’t the only thing that makes him healthy. The hospital sends my dad a survey about his long COVID recovery every two or three months. As I read the survey to him and translated it into Spanish for him, I felt like we were going somewhere we’d never been before.

“Have you ever felt bad about going to the hospital?”

“Has the way you feel about your body made you nervous?””

I’m wondering if he will be open to or even willing to talk about these things. My father rarely talks about how he feels, and the older I get, the more I realize that this is because of how people in his culture view mental health. In some ways, he is like the stereotypical Latino father: he is quiet, doesn’t say much, and keeps his feelings to himself. As a child, when I told my father I loved him, he would always say, “Don’t tell me you love me; show me.” a phrase that has always shown how we feel about each other. As I got older, I learned from him not to show him how I felt, and I did the same. Instead, I went to my mother when I needed to let off steam or talk about my worries.

All of that changed in a big way when my dad got sick two years ago with what we thought at first was a bad seasonal cold. A week later, he couldn’t breathe. He went to Etobicoke General Hospital, where doctors told him he had COVID-19-related double pneumonia. I called for the ambulance, and from then on, I was the main person the hospital staff talked to about my family. I wanted to have the same level of calm that I had seen my father have his whole life. I wanted to be a strong point for my family during this hard time, so I did my best to keep my feelings from getting in the way of the role I had to play.

As my dad’s health got worse, he was put on an extracorporeal life support machine for 56 days. Each time we went to the hospital, it got harder and harder. I would sit next to my dad and watch the plastic tubes that went from the artery in his neck and his windpipe to an artificial lung machine on the right side of his bed. He was completely asleep, and his face was a little bit swollen. The quiet me didn’t say much, but I held his cold hand to try to give him some of my energy.

Every time I saw his vital sign numbers on a machine above his hospital bed, I wondered if this was my last time with my father. I asked myself if I was happy with our relationship. Even though I knew he wouldn’t answer, I wanted to tell him one last time that I loved him.

The loss of parental love, or even the possibility of losing it, can change our emotional space in a big way. During those months, I felt a wide range of emotions, including emptiness, loneliness, guilt, and even anger. And it wasn’t until my dad was moved from the ICU to a rehab center that I finally let myself feel all those feelings I had been afraid to feel.

It had been five months since he was admitted to the hospital, and I cried for the first time since then. It was a cathartic experience that changed my ideas about how to feel and show my emotions.

When my dad finally got out of the hospital and went home, he made quick progress in getting better. In the first two months, he went from being able to use 40% of his oxygen to being able to use 60%. But as his physical recovery stopped making progress, I could see that my dad was having a hard time accepting that some parts of his recovery were out of his hands. I wanted to tell him that being dependent on others didn’t mean he was weak.

So, when we get to the question about his mental health on his hospital survey, I feel a twinge of awkwardness or reluctance, but I push it aside. I really want to be honest in our relationship, and that has helped my dad be more honest about how he feels.

Even though we talk about his emotional well-being in the context of his physical recovery, this has helped our whole family talk more openly about how we feel.

In answer to one of the survey questions, my dad says, “Even on my good days, I tend to do too much.” “I’m learning to deal with the internal conflict between wanting help and feeling like I’m a burden on others.”

He stops, then looks up at me.

“But I don’t worry about not being independent because I know I have people who care about me.” “In moments of need, I know I can be honest,” he says. As I write down his answer, I smile back at him with happiness.

Do you have a compelling story about yourself that can help others understand or learn something? We want to know what you think. Here’s more information about how to get in touch with us: