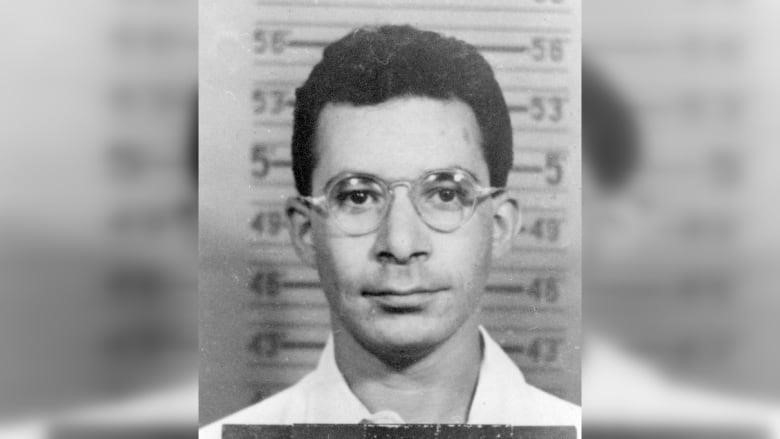

A physicist from North End who was hired for the Manhattan Project put together the world’s first atomic bomb

The hit movie from HollywoodOppenheimer Is selling out theaters and getting great reviews, but a connection to Winnipeg has stayed behind the scenes.

The movie tells the story of Robert Oppenheimer, a theoretical physicist who was in charge of the secret Manhattan Project, which led to the start of the Atomic Age.

Oppenheimer was in charge of the Los Alamos lab where the work was done, but it was Louis Slotin, from the North End neighborhood of Winnipeg’s Scotia Street, who put together the Trinity Gadget, the first atomic bomb.

“He died before I was born, so I never met him in person, but my family always told me about him, and I thought he was very brave and should have been a hero,” said Israel Ludwig, whose mom was Slotin’s sister.

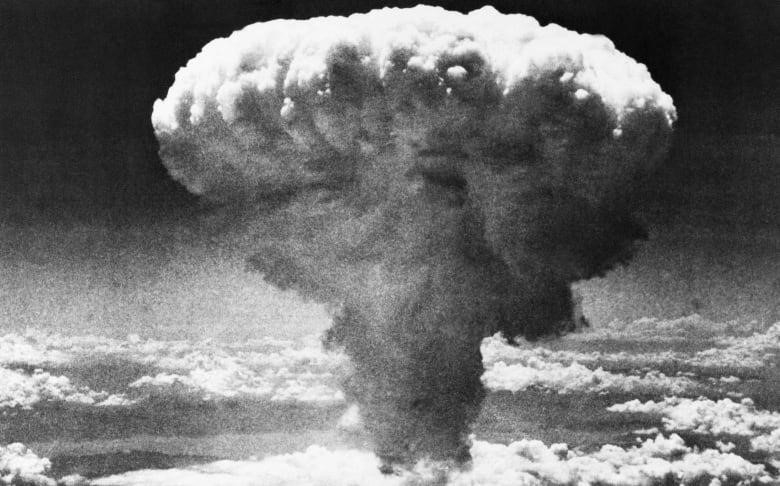

On July 16, 1945, Trinity was dropped at a test site in the desert of New Mexico. It worked so well that a month later, the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan were bombed.

The exact number of people who died because of the atomic bombs will never be known, but it is thought that between 129,000 and 226,000 people died. About 120,000 died right away, and tens of thousands more died over the next few months from burns, radiation sickness, illness, and lack of food.

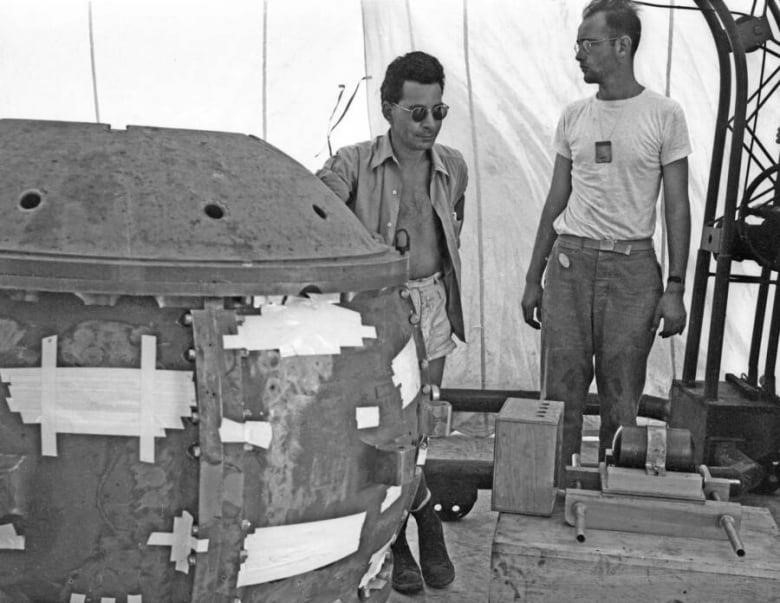

Ludwig said that the Oppenheimer film has a short black-and-white clip of Trinity being put together. In the middle is Slotin, but his name isn’t said and there are no credits.

Martin Zeilig, a journalist who wrote about Slotin and made a documentary about him, called him the “chief armourer of the United States” because he was so good at making bombs.

“But most biographies of the Manhattan Project don’t talk about Louis Slotin. Zeilig said, “He was working with all these great scientists.”

“It might be hard to get your name into the history books when you’re in that kind of atmosphere.

“That’s one of the main reasons to tell this story and teach a new generation about the role of this scientist from Winnipeg. He was a great person. I’m getting pretty upset just thinking about it.”

Slotin was born in the North End. He went to the University of Manitoba when he was 16 and got his master’s degree in science when he was 22. In England, when he was 25, he got his PhD in physical chemistry.

He went to the University of Chicago and helped build the first cyclotron in the Midwest of the United States. He was then asked to lead the team that made the plutonium core for the Manhattan Project.

A year after Hiroshima and Nagasaki were bombed, Slotin’s team only had one core left. It was about making a third atomic bomb, but Japan gave up and the war ended.

The core was saved, and it was used to study nuclear fission.

Ludwig said that Slotin had given notice that he no longer wanted to work on projects that were meant to hurt people.

“He wanted to go back to Chicago University. He was interested in how radiation could be used to fight cancer, and he also wanted to look into how it could be used to help fight other diseases, Ludwig said.

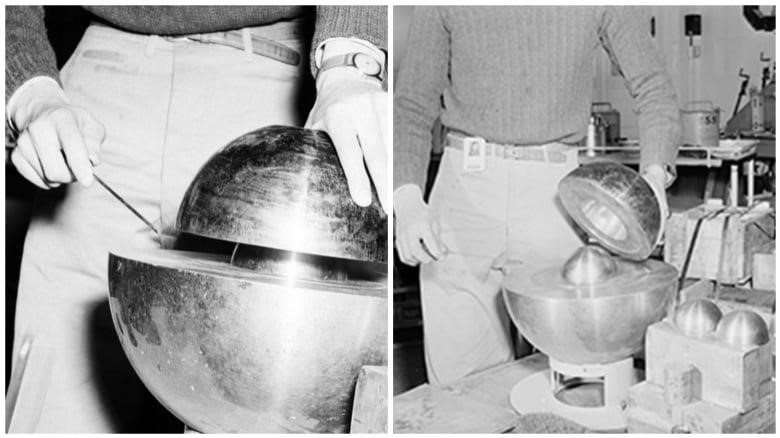

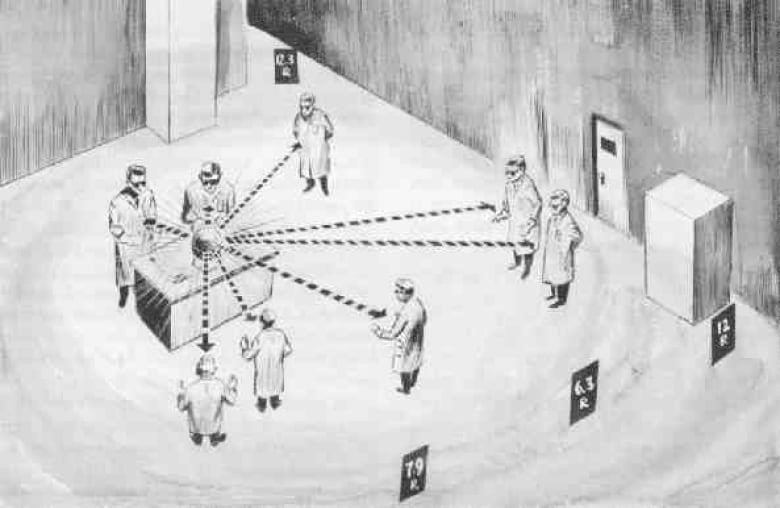

On May 21, 1946, just before 3:30 p.m., Slotin was showing his coworkers how to get the core close to a fission reaction, a process called “ticking the dragon’s tail.”

It was done by putting two beryllium half-spheres around the core. As the two halves moved closer to the core, the amount of fission increased. This brought the materials close to starting a nuclear chain reaction, which is called a “criticality test.”

Slotin used a screwdriver to keep the two pieces apart. He had done this process many times before, but the screwdriver slipped this time. When the two pieces touched, there was a critical reaction right away.

The Los Alamos National Laboratory and the Los Alamos Historical Society say that there was a flash of blue light and heat in the room.

Slotin put his body in front of the sphere to protect his fellow scientists. He then pulled the two halves apart, stopping the chain reaction before it could reach the supercritical stage and cause an explosion.

Even though Slotin only saw the light for a second, it was enough to kill him.

He was exposed to almost 1,000 rads of radiation, which is a lot more than the 400-450 rads that are thought to be a lethal dose. In 2016, Zeilig wrote an article for Canada’s History magazine called Dr. Louis Slotin and the Invisible Killer.

Slotin was taken to the hospital right away, but nine days later he died. He turned 35.

The radiation burned his body on the inside and outside so badly that one doctor called it a “three-dimensional sunburn,” according to Zeilig’s article.

The seven other people in the room were probably exposed to between 90 and 166 rads. Everyone made it.

“He didn’t hesitate for a second, even though he knew he would get hurt. He jumped in to stop the chain reaction. Ludwig said, “You can’t think of a higher sacrifice than giving up your own life to save others.”

Before the accident, the plutonium orb was jokingly called Rufus. After the accident, however, it became known as the demon core.

The U.S. government called Slotin a hero because of what he did, but some people disagree with that because they say he was careless and caused the accident.

“They already had ways to do it mechanically, but he liked to work with his hands, so he wanted to do it himself,” Zeilig said. “I say it with love. He was someone who took risks.”

Zeilig said that he had a “amazing mind” and that he was a Jewish kid from the North End who helped change the course of human history.

And that’s how he wants people to remember Slotin: “That he was an important part of making science and knowledge better or worse.”

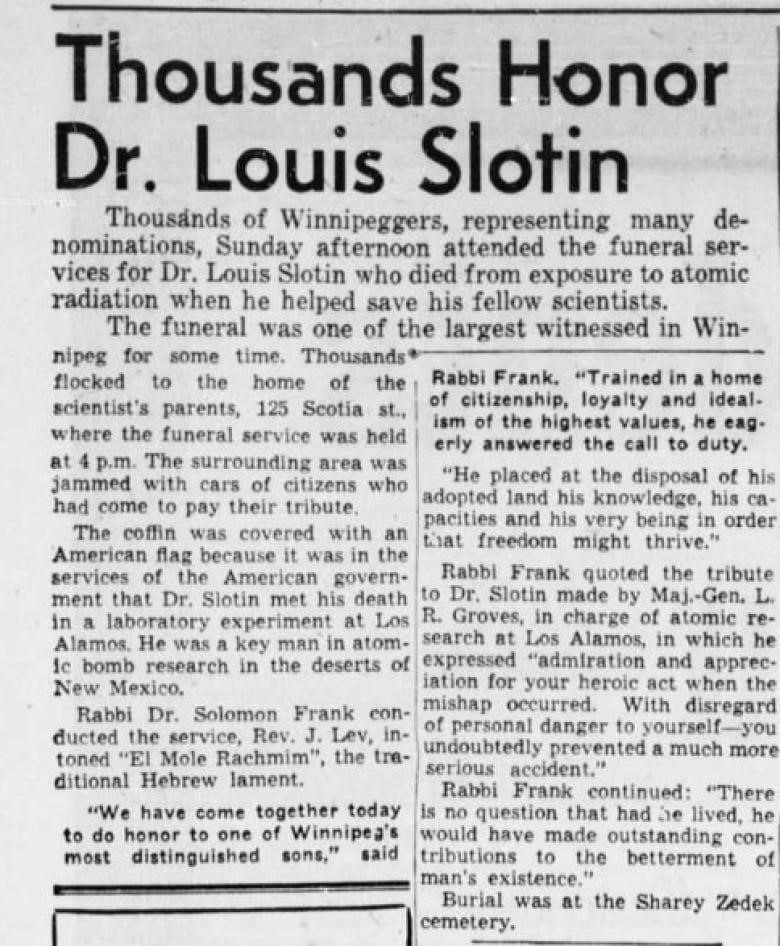

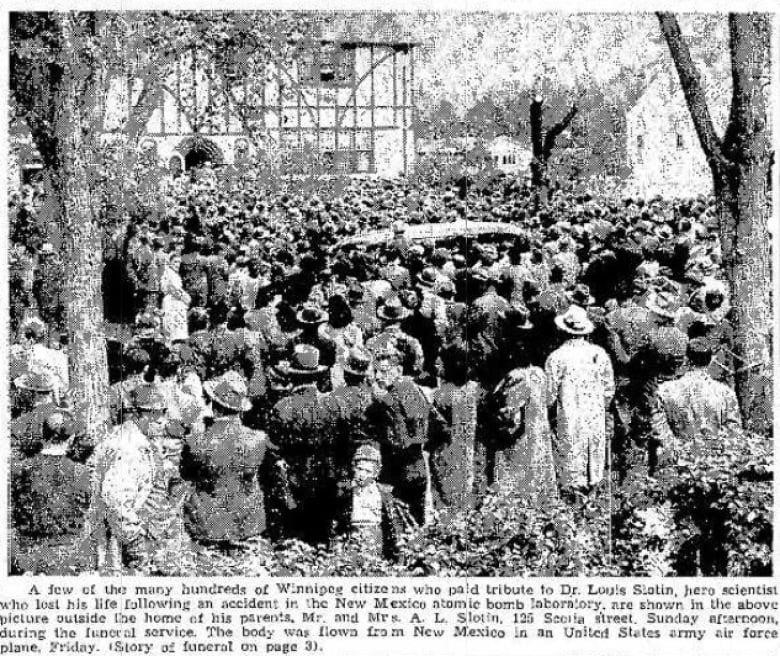

As was Jewish custom, Slotin’s funeral was held at his family’s home on June 2, 1946. An article in the Winnipeg Tribune the next day said that thousands of people came to pay their respects.

Ludwig said that there were so many people outside the house that you couldn’t see the yard or the street.

Before Slotin was buried in Winnipeg’s Shaarey Zedek Cemetery, the rabbi called him “one of Winnipeg’s most distinguished sons,” according to a Tribune article.

After the accident, no more critical assembly work was done by hand at the Los Alamos lab. After that, machines that were controlled from a distance were used to test the criticality of fissile cores.

It happened in a building that is now called the Slotin Building. It is part of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park and has been kept in good shape by the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Dr. Louis Slotin Memorial Park is in Winnipeg. It is at the end of Luxton Avenue and looks out over the Red River.

Half a block from the old Slotin house on Scotia is a small area with benches and a plaque.