Indigenous elders say that the only way to make change is through knowledge

When Sheila Joris walked into her local Ikea store and saw a colorful display of books, the artwork on the fabric book covers caught her eye right away.

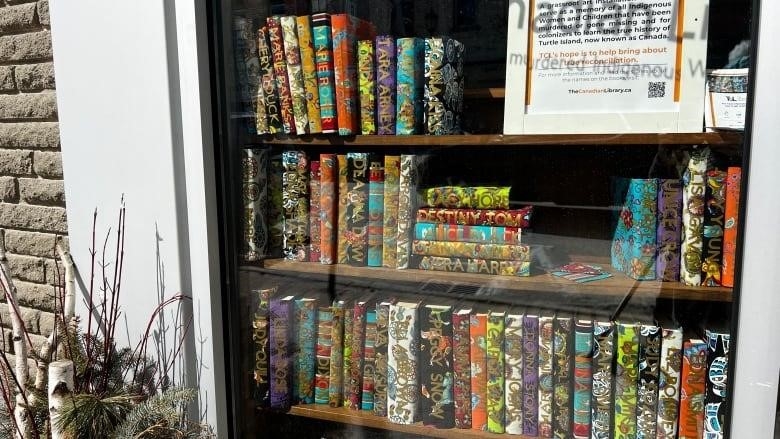

The bright gold letters on the books that listed the names of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls from all over Canada got her attention.

After doing more research, the owner of a business in Strathroy, Ontario, was “astonished” to find out how many women and children had disappeared and what had happened to them. It made Joris want to show the display in the front window of her downtown shop, KYIS Embroidery, to bring more attention to the issue.

She said, “It’s just a way for me to show that I care.” “Some of these families didn’t get any help to find their loved ones, which I think is very sad. The world needs to hear their stories.”

The Canadian Library (TCL) project is being done in many places across the country, including Joris’s shop. A small art installation with the goal of bringing more attention to the MMIWG crisis.

WATCH | Businesswoman Sheila Joris talks about why she cares about MMIWG’s stories:

Shanta Sundarason, a Toronto-based activist who is leading the grassroots project, said, “The only way we’ll ever reach reconciliation and break down barriers is if everyone gets educated, and that starts with these important conversations.”

Since they began their work in October 2021, participants have gotten donations of books of any kind. They order fabric covers made by Indigenous artists, and each one has the name of an Indigenous woman or girl who has gone missing or been killed.

So far, more than 8,000 books have been brought in. Sundarason said that they will be put on display at a national museum or gallery by the end of this year. She also said that she wants them to be used as a teaching tool to remember the people who died.

Building trust between settlers and Indigenous people will take a lot of work.– Shanta Sundarason, who started TCL.

Sundarason moved to Canada from Singapore 12 years ago. She said that as an immigrant, she felt it was her duty to learn about the stories of residential school survivors and the systemic discrimination that many Indigenous people still face.

“It was horrifying to learn that so many people in a country like Canada still don’t have clean water to drink, and so much has happened to these communities,” she said.

“It will take a lot to build trust between settlers and Indigenous people who have been trying for decades to tell us their stories.”

TCL is on display in every Ikea store in Canada, as well as in cafes, hospitals, and, most recently, at the York Region District School Board. Sundarason said.

Elder calls it a step toward peace for everyone

Elders from Indigenous groups have given TCL a lot of support. Sundarason said that at first, many of them were skeptical about the project, but they eventually gave their advice to the team working on it.

In Calgary, TCL is led by linda manyguns, a Blackfoot woman from the Siksika Nation in southern Alberta who spells her name with only lowercase letters to honor the Indigenous struggle for recognition.

Manyguns, who is also the associate vice president of Indigenous and decolonization at Mount Royal University, said she was impressed by TCL’s ability to include everyone and bring the MMIWG crisis to the forefront in a way that focuses on the voices of their family members.

“There is a huge gap between the Canadian society as a whole and the experience of the Indigenous people,” she said.

“People need to know that these women aren’t bad. They’re just stuck in a social situation that was created by colonial views and placements of Aboriginal people, which puts them in situations that make them vulnerable.”

Manyguns said that TCL makes a place for the MMIWG’s memories to live on and gives Indigenous artists a place to shine because the artwork draws all kinds of people.

“It’s a step toward reconciliation for everyone because it’s an ethical third space where people can meet to work together and make new frontiers. We can only bring about change if we know what to do.”

She hopes that TCL can get enough people to work together to make changes so that more Indigenous women and girls’ names don’t get added to the list.