Scientists say that because the climate is getting warmer, most species of tunicate are in the Maritime

Scientists are keeping an eye on dozens of sites in Nova Scotia and southern New Brunswick to see if the last warm winter in Atlantic Canada sped up the spread ofMarine creatures that are slimy.

In the last ten years, Nova Scotia has become home to six species of sea squirts, also called tunicates. It is thought that two more have arrived.

The creatures stick to everything they touch and have become a big problem in the shellfish aquaculture industry.They are 95 percent water and very heavy, which makes ropes sag and makes it more likely that gear and goods will be lost during storms.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that most of these species are here because of the warming climate,” said Claudio DiBacco, a federal researcher at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography in Dartmouth, N.S., who specializes in aquatic invasive species.

Tunicates are sacks full of organs and water that are good at filtering food, making more of themselves, and “biofouling,” or sticking to things like boats and underwater pipes. The name “sea squirt” comes from the way they shoot water when poked or prodded.

Most of the invasive species come from ships and their ballast water.

Nolan D’Eon, who grows 1.4 million oysters every year on his farm in Argyle, N.S., now has to deal with tunicates all year long.

“Some tunicates are in the cages. Right now, they are very, very small. But we never let them grow,” D’Eon said as he looked at an oyster cage that had been pulled onto a service boat in Eel Lake.

His solution is to turn each cage upside down for 48 hours and let the sun and heat kill the tunicates, but they always come back.

“Tunicates are giving birth at a time we’ve never seen before. And in the winter, they all used to turn green. All of them were dead by spring. Now that you’ve opened your cages, you can see that they’re all still alive. “They don’t die in the winter, which means we have to do a lot more work,” said D’Eon.

Also, the creatures don’t look good.

“Scraping tunicates off mussels is my life,” Peter Darnell, a veteran mussel and scallop farmer in Mahone Bay, N.S., joked. “There are just so many. They have a lot. They can’t be true. They give birth twice a season, so there are two groups of billions of them in one year.”

Fisheries and Oceans Canada checks between 50 and 70 places to track the spread and survival of invasive tunicates. These places are in northern Cape Breton, along the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia, and in southern New Brunswick.

Under public wharves, aquaculture sites, and even inside the marine protected area in the Musquash Estuary near Saint John, there are metal plates hanging in the water.

Site 1 is the name of the busy fishing port in Digby, Nova Scotia.

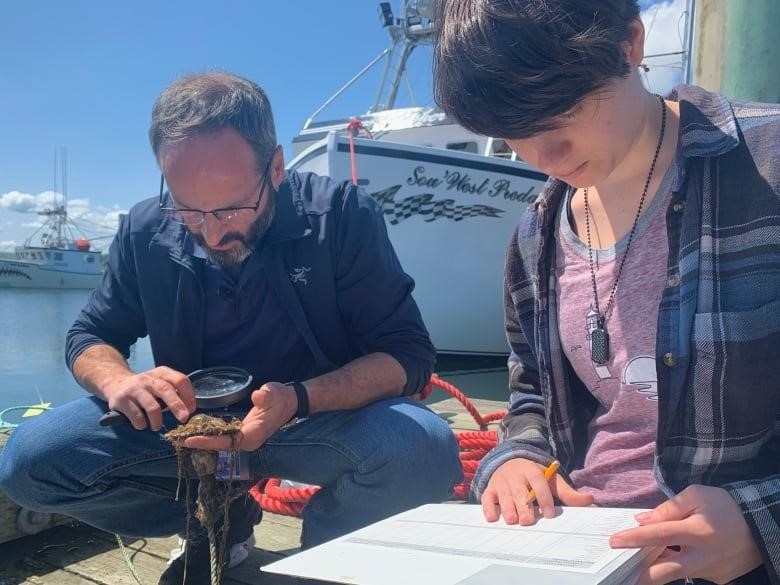

Biologist DiBacco and technician Neo Paulin from Fisheries and Oceans Canada recently pulled a plate that had been hanging for a year under a floating wharf in the harbor. It came out with six different kinds of tunicates all over it.

“This is the front for the invasion of Nova Scotia. “This is where most of our species show up for the first time, because most of them are moving north from the Gulf of Maine,” said DiBacco.

“This is a good time to come see them because they have never been in cold water because the winters are warmer and this part of the province is the warmest.”

People are keeping a close eye on the diplosoma listerium, the European sea squirt (ascidiella), and the pancake batter tunicate (didemnum vexillum).

The pancake batter tunicate was one of the first to be seen in 2013. This was one year after the Gulf of Maine and Atlantic coasts had their warmest year on record.

In 2015, a cold winter slowed down the tunicates, but it did not stop them.

‘Thermal refugees

They made it through the next cold winter in 2019 by going to places called “thermal refuges” where the water is just a little bit warmer.

DiBacco and other scientists built a model to predict the spread based on temperatures by looking at where diplosoma stayed over the winter at three monitoring sites in southern Nova Scotia.

The model was used to find places to keep an eye on tunicates, and it is now being improved to take growth and reproduction into account.

Back in Mahone Bay, Darnell says that invasive tunicates don’t bother him.

He has been dealing with them for many years, including ciona intestinalis, a sea squirt that looks like a slug and that he first saw about 15 years ago.

“Well, it doesn’t really matter. Out there, there’s no more room for anything. I guess it doesn’t matter much if something takes the place of something else. Everything we put in the water gets loaded with something.”

Ballast water discharge rule

Still, even he is surprised by how fast the disease is spreading.

He said that DiBacco, a scientist from the federal government, recently found ascidiella, also called the European sea squirt, in a different part of Mahone Bay, away from his leases.

“In October of last year, he saw a new tunicate called ascidiella. It was another one that lived alone. Similar to the other ones in size. That was pretty cool. They had seen them in Lunenburg Bay before, but I had not. This year, it’s a toss-up. They are almost as many as ciona. Wow.”

In response to worries about invasive species like tunicates, Canada is putting in place rules for the shipping industry about ballast water discharge, telling commercial and recreational boaters to be more careful about cleaning their hulls, and keeping an eye on aquaculture transfers.

When DiBacco was in Digby, he looked down at a plate full of biofouling and saw the beauty in it.

“If I point to the gold star, that’s this one that looks like a star. “Each of those lobes is different, and the shape is so beautiful,” DiBacco said.

“If you get to look at these up close, not just through a microscope, the reds and browns are just so pretty. I know they’re slimy, but if you can get past that, you’ll find that they’re a beautiful and diverse group of people.”

MORE TOP STORIES