After siblings’ health card notices were taken from their homes in 1976, the sister said, “I know he’s out there.

Since he was taken away as a child during the Sixties Scoop, a Métis man has been missing for decades. His siblings want to know why the Manitoba government keeps sending him a verification of address request to the same home they took him from more than 45 years ago.

Sandra Myers said, “Even though my parents have been dead for years, his health card keeps coming in the mail.” “Someone is aware of something.”

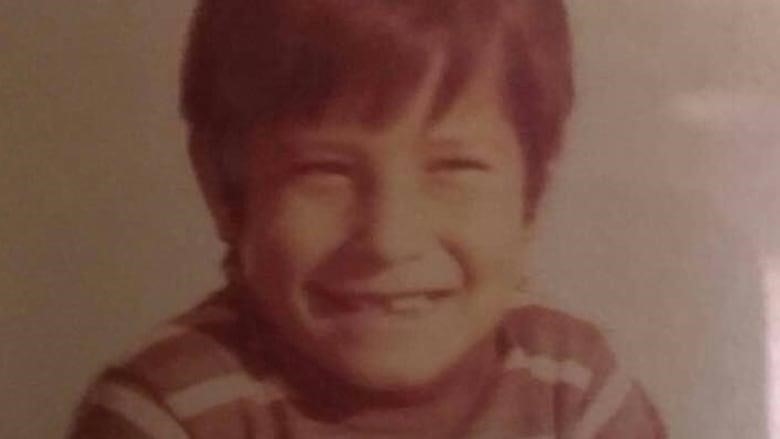

In 1976, child welfare workers took Alex James Sutherland and his six siblings from their Camperville, Man., home. Alex was only five years old at the time.

It was part of the infamously terrible Sixties Scoop, in which thousands of Indigenous children were taken from their homes and put with non-Indigenous families as far away as the U.S. and Europe. This happened from 1951 to 1991.

They say that Alex and his siblings, including Myers, were taken against their will. Child welfare workers said that their father drank too much and hurt them.

“I’m kind of shocked,” said Myers. “I don’t remember any mistreatment.”

Their mother, on the other hand, thought the worries were only temporary and agreed to sign a paper that would let child welfare workers vaccinate the kids.

Instead, she gave up her rights as a parent by signing a paper.

“My mom couldn’t read or write, but they gave her paper and a pen,” said Marj McGillivray, Sutherland’s sister. “She didn’t even know that she was signing us away.”

A curious clu

Myers and his two brothers and sister were all adopted in Louisiana. McGillivray stayed in Manitoba and moved from foster home to foster home until she was a teenager and could go live with her parents again.

But no one ever heard from Alex Sutherland again.

McGillivray says, “I hear from the other ones, but this one just left.”

In 2016, the siblings told their story to CBC and went public with their search.

As the story spread over the years, so did the tips. A couple of Alex’s old friends from Mafeking, Man., who went to school with him as a child reached out to say hello.

Later, the kids heard that Alex was in Thompson, Manitoba. They heard he might be in Alberta another time. On another occasion, Ontario.

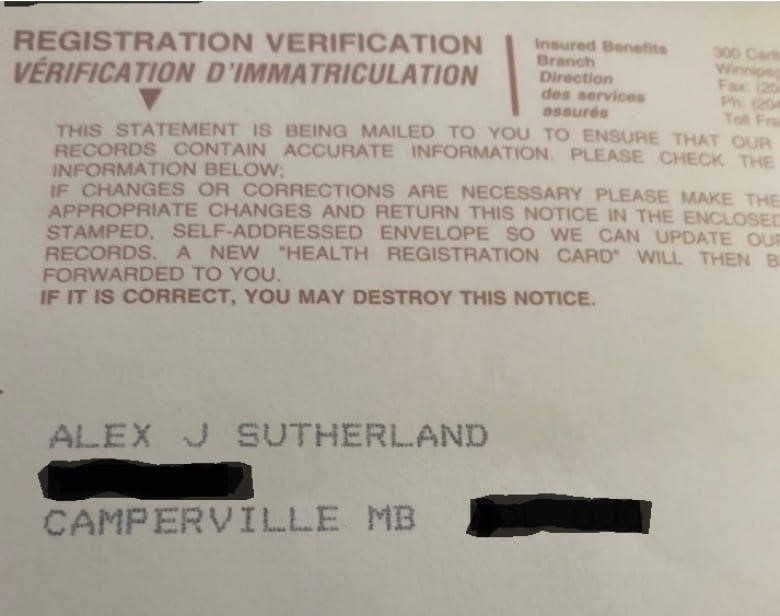

Then, a few years later, a strange clue showed up in their parents’ mail box.

The province started sending Alex James Sutherland health card registration verifications. These were sent to his childhood home in Camperville.

They are still coming as of 2023.

“That’s why my mom and dad thought he was still alive and living in Manitoba,” McGillivray said.

Now, Sutherland’s family wants to know why a provincial department is sending mail to his childhood home, as if that was his last known address, as far as the province is concerned.

‘I’m not giving up hope

In a written statement, a provincial spokesperson said that if a person hasn’t used their Manitoba Health card in the past 12 months, the province sends a verification notice to the last address it has on file “to make sure their address is still current and there are no new changes to their health card.”

A spokesperson said that if the notice comes back marked “return to sender,” the health card is taken away.

They wouldn’t say more about whether or not they would send a verification for a health card that hadn’t been used in over a year.

“We’re getting into hypotheticals here, which we can’t comment on,” the email statement said.

The Manitoba Métis Federation also has questions about Sutherland and has offered to help the family find the answers.

Frances Chartrand, vice-president of the northwest region, said in a written statement that the federation is “happy to work with the family to find out what’s going on.”

“It makes us sad every time we hear that Sixties Scoop survivors from our area haven’t found their way home yet.”

Chartrand said that the Métis Federation’s Sixties Scoop department can give the family “wraparound programs and services” that are made to fit the needs of each survivor.

Myers said that she would be thankful if the federation helped her.

“I’ll be glad if anything helps to find him,” she said.

“I looked for him all the time.I’m not giving up on things. I’m sure he’s somewhere.”

She also wanted to tell her brother something.

“I’m reaching out to you, and if you can hear this, look me up on Facebook,” says Myers. “Know that I won’t give up until I either find you or know where you are.”