The Toronto District School Board says it is making a policy based on what Indigenous communities have said

A former student and a parent of Kapapamahchakwêw – Wandering Spirit School in Toronto want Canada’s largest school board to make a policy that vets applicants who say they are Indigenous and want to work at schools or programs that focus on Indigenous people.

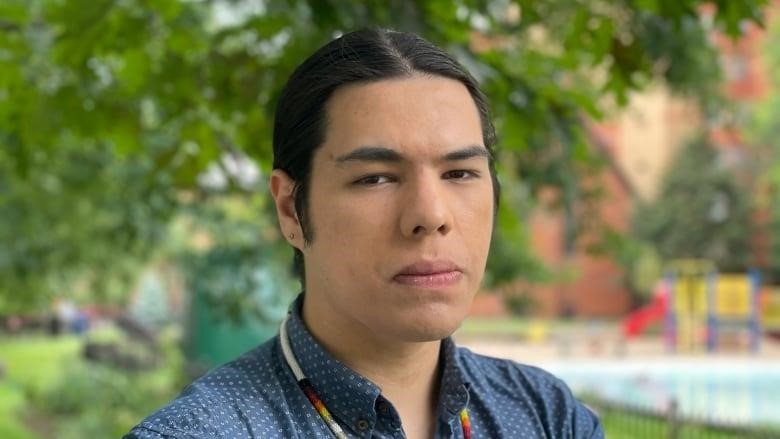

Michael Peters just graduated from Wandering Spirit. He says that in his later years there, some students started to argue with a teacher who was “claiming to be Indigenous.”

“It really changed how the students learned and how Indigenous people were taught, because if these people aren’t Indigenous, how can they really teach through an Indigenous lens?”

As of right now, the Toronto District School Board (TDSB), like many other employers, relies on those who say they are Indigenous to identify themselves on their own.

There is no policy or screening process for people who say they are Indigenous and want to work at schools like Wandering Spirit that focus on Indigenous education and immerse students in Indigenous culture and traditions.

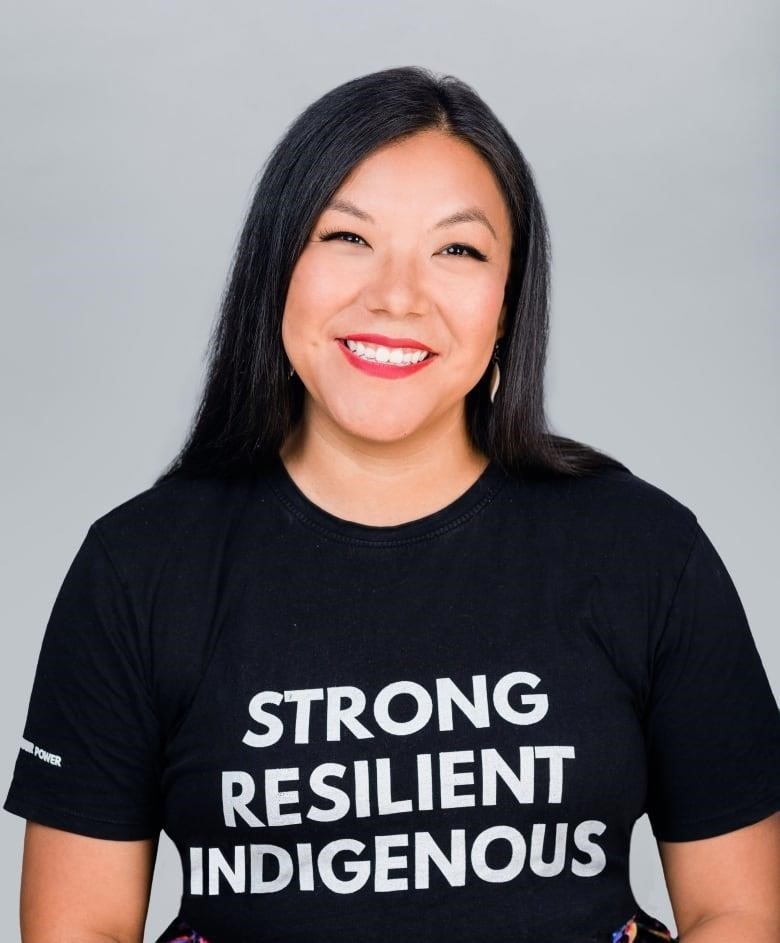

“The policy says that anyone who says they are Indigenous has to be taken seriously. “There’s no screening,” Deanne Hupfield said.Her kids went to Wandering Spirit, and her husband, John Hupfield, is also the head of the parent council at the school.

Deanne Hupfield used to work at the TDSB’s Urban Indigenous Education Centre, which is in the same building as Wandering Spirit and helps shape the TDSB’s curriculum and connects Indigenous students with services.

“It’s a growing problem in the Indigenous community that people just self-identify, come into our communities, and take positions of power,” she said.

TDSB says it is “working on a procedure.

The TDSB told CBC Toronto that it is working on a policy that would take into account who is on staff. It also said that Wandering Spirit’s parent council helps decide what questions to ask people who want to work at the school during their interviews.

“The Kapapamahchakwêw-Wandering Spirit School Care Givers Circle (Parent Council) has been giving advice. The TDSB has said in a statement that it is in the early stages of making a procedure that will be based on input from Indigenous communities.

John Hupfield, who is in charge of the parent council, says that the principal met with the group in May 2023 to talk about hiring standards. He said that the council was worried about staff who said they were Indigenous and what that meant for children.

“Especially brand new teachers with little teaching experience getting jobs at WSS with unclear ties to Indigenous Nations/communities,” John Hupfield wrote in a statement to CBC News. “And the government was willing to talk about our worries.”

He said that the council gave feedback on one of the interview questions, but that “at this point, the Indigenous community does not have any control over these decisions or the power to make them.”

Students asked some staff members who they were

Peters is Anishinaabe and comes from Long Plain First Nation in Manitoba. He went to Wandering Spirit for the first time in 2017 when his family moved back to Toronto.

Before that, he remembers that he was the only Native American in his class. He says that he and his mom thought it was important for him to learn more about his culture, so he went to Wandering Spirit.

“It’s hard to stay connected to your culture when you’re Indigenous and you move to a big city like Toronto,” he said.

“I can say that after going to Wandering Spirit, I have definitely gotten back in touch with my culture. I have started to learn my language, which is a big step. So, going to school helps with that.”

But Peters says that as time went on, there were fewer Indigenous staff, and he and other students would talk about how they didn’t want to take classes taught by people whose Indigenous identity was in question.

Peters is in the process of becoming a teacher so that he can work at Wandering Spirit. This fall, he will do a practicum at the school.

He says he hopes that more education about Indigenous history, culture, and experiences will keep non-Indigenous people from pretending to be Indigenous when they are not.

“I think that will make a lot of people less likely to say they are us, since they will realize they haven’t been through any of this.”

Experience and cultural connection are very importan

Deanne Hupfield is Anishinaabe and lives in the Temagami First Nation. She has sent five of her children to Wandering Spirit, and three of them will be back in the fall.

“They have really amazing Indigenous teachers,” she said, adding that the school is a great place to learn about culture.”They get language every day from an Anishinaabe kokum.”

But she was worried about the identities of two teachers at Wandering Spirit who called themselves Indigenous.

After talking to those teachers, she asked if they were Indigenous and, if so, if they were part of an Indigenous community and what their cultural ties were.

She says that she asked one of the teachers if they were from a certain group, and the teacher told her that they were still learning about their background.

“My Indigenous children are being led by people who have never been Indigenous and have no ties to any living Indigenous community.”

Deanne Hupfield says that her mother was part of the Sixties Scoop and that most of her grandparents and great-grandparents went to residential schools.

“That caused a lot of trauma across generations,” she said. “Because of that, my life was very hard.”

Even though there are non-Indigenous people working at Wandering Spirit, she and Peters say they have no problem with that. They are just worried about people who might be lying about who they are.

WATCH | A report looks at how Indigenous identity fraud hurts people:

A Métis lawyer says that making false claims can hurt people

According to a report that Indigenous rights lawyer Jean Teillet wrote in 2022, she thinks that tens of thousands of people in Canada lie about being Indigenous.

She told CBC Toronto, “There’s no way to know for sure, so let’s just say it’s a big problem.” “It’s not just these isolated cases that are getting a lot of attention.”

The University of Saskatchewan (U of S) asked Teillet, who is Métis and the great-grandniece of Louis Riel, to write a book.write a report, which she called “Indigenous Identity Fraud,” during a scandal at the school about a professor’s Native American identity.

She says that some people pretend to be Indigenous in order to get jobs, gain prestige, or make money. She also says that it hurts Indigenous people by taking away their chances and platforms.

“This is going to cause a lot of harm,” she said. “It has a huge impact on everything going on in our schools and on the policies that the government is making. And it always seems to hurt Indigenous people.”

Teillet says that if someone says they are Indigenous, they must be accepted by the people they say they are a part of. She says that having even a small amount of Indigenous DNA doesn’t make a person automatically Indigenous.

“There’s no real connection to the culture and no lived experience,” she said.

Some schools have verification systems in place

Some Canadian universities, like the University of Saskatchewan (U of S) and the University of Waterloo (UW), have their own verification systems for people who want to apply for jobs, scholarships, or funding that are only for Indigenous people.

Indigenous communities and governments check a person’s citizenship or membership as part of the verification process at both schools.

The U of S launched an online portalThat lets people upload proof that they are part of an Indigenous group. The university says that a status or citizenship card is an example of proof, but other things, like an oral history, could be accepted for people who don’t have proof.

At UW, if there is no documentation, requests for verification will be looked at by a committee led by Indigenous people.

Teillet says that relying on self-identification alone is “what got us into this mess in all of our institutions,” and that the way out is to ask for proof of your identity.