First Nations in Saskatchewan can now see how much Crown land is being sold off in their area

First Nations in Saskatchewan say that the provincial government is keeping them in the dark as it sells off land in their traditional territories.

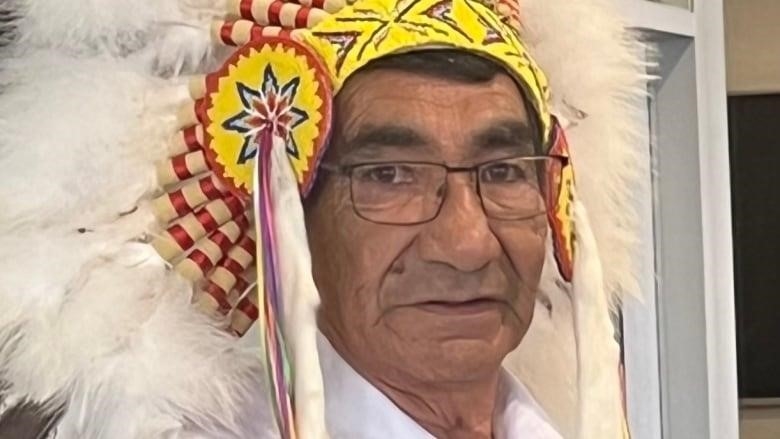

Chief Henry Lewis of the Onion Lake Cree Nation said, “They started selling land without telling us.”

Lewis and others had heard that small pieces of public or “Crown” land were being sold or rented out, but they didn’t know how big the problem was.

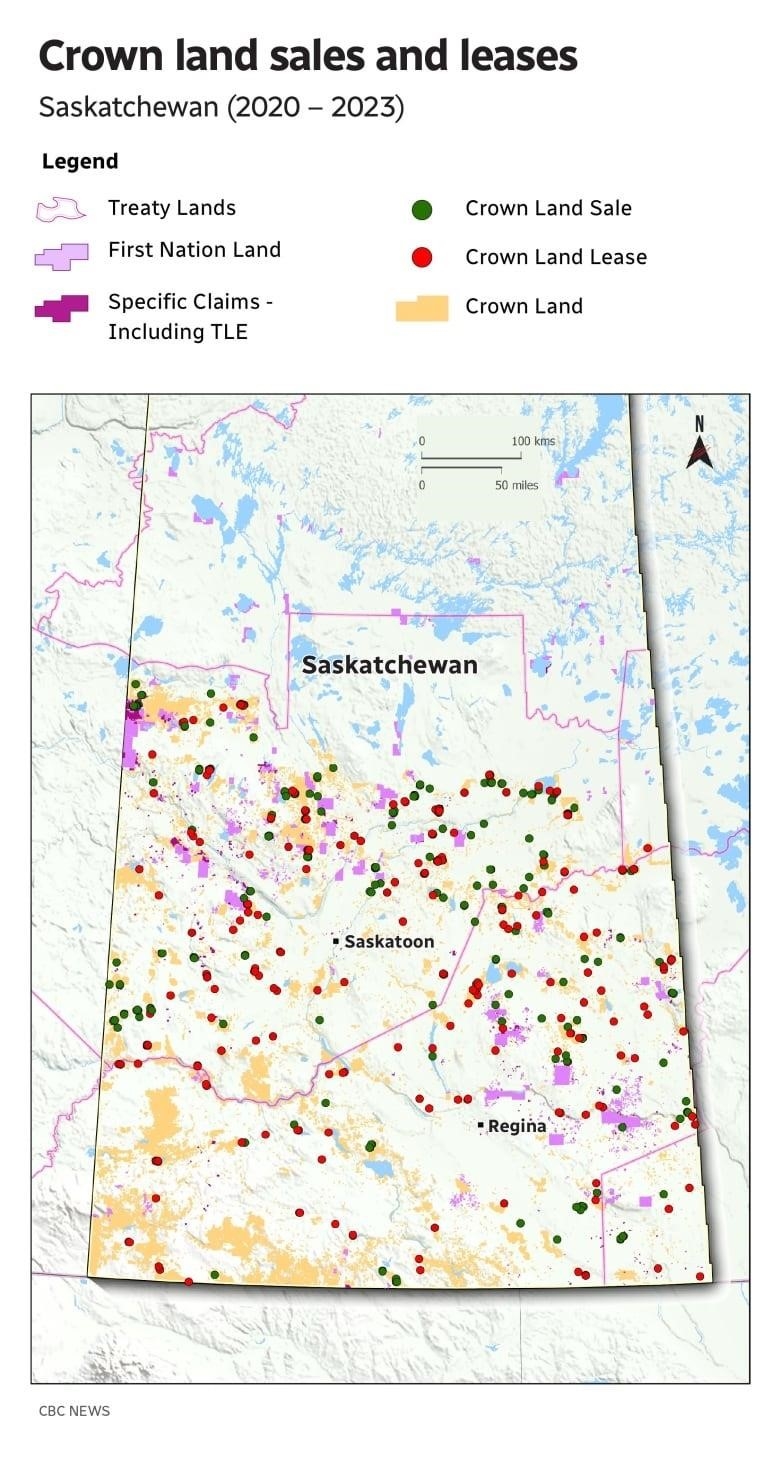

All of that is changing. The Saskatchewan First Nations Natural Resources Centre of Excellence made a complete set of maps that give them new tools in this fight.

It is the result of hundreds of hours of gathering and analyzing data at the center’s office outside of Saskatoon.

The center is giving the maps to every First Nation in the province. They show the exact location and size of Crown land sales.

From Meadow Lake in the north to Estevan in the south, there are red and green dots all over south and central Saskatchewan. These dots show sales and leases.

The centre found that the provincial government has made at least $84 million from selling off Crown land over the past 10 years.

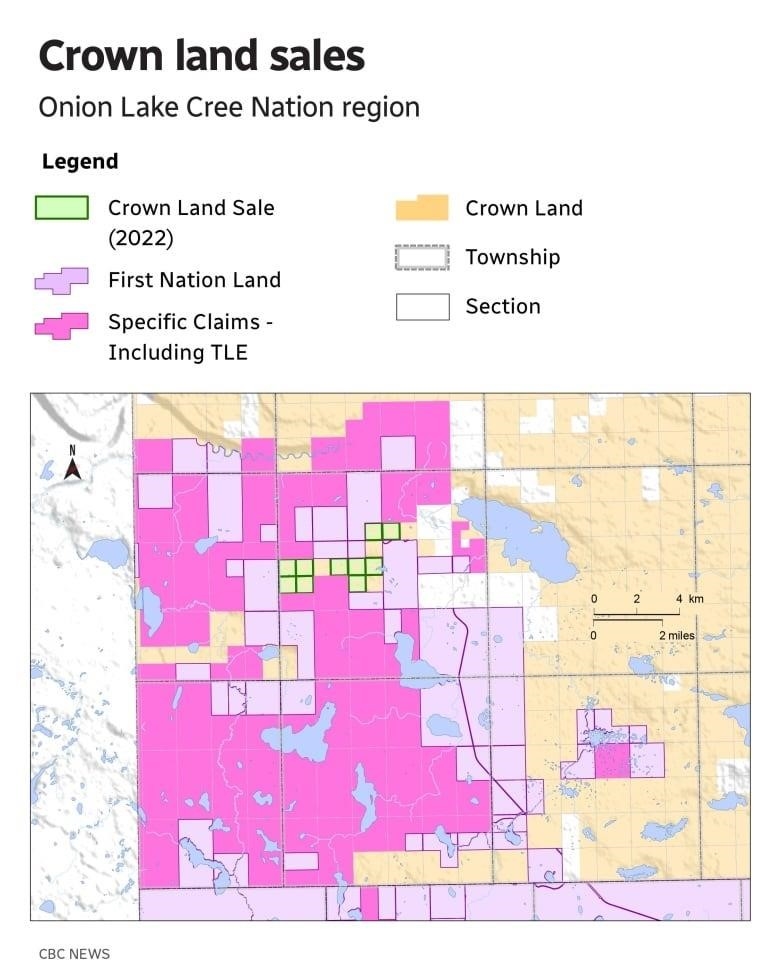

On the maps, Lewis could see that pieces of land close to his reserve had been sold off. But land was also sold near the town of Onion Lake, which has more than 4,000 people and is 300 kilometers northwest of Saskatoon.

He said that he tried to find out what was going on, but nobody would talk to him.

“We were the first ones to know, but many other Nations didn’t know what was going on. We tried to stop the sale of Crown land for a while, and I think it worked,” Lewis said.

When Onion Lake asked the government to stop selling, Lewis said that they had promised to do so. Lewis said that instead of selling the land, the government is now renting it out for up to 33 years.

In the past year, they have done this on more than 40 pieces of land across the province, and there are plans for another 50, according to officials from Onion Lake. Lewis and other leaders of the First Nations said this is not true.

WATCH | First Nations now have a new way to fight for their land claims:

The first maps were made with the help of Onion Lake’s duty to consult coordinator, Terry Quinney. She said that they had to fight with the government just to get the raw data.

She said, “We want Nations to know what’s going on right in front of them.”

Lewis and other people say that this selling-off must stop right away for two reasons.

First, the numbered treaties, which were signed mostly in the 1870s, gave Native Americans the right to hunt, gather, and fish on public lands. This was made even more clear by the Natural Resource Transfer Agreement, which was passed in 1930. When land is sold to private owners, it is no longer available. They say that the provincial government’s new, stricter trespassing law makes it harder for them to live their traditional ways of life.

Second, after these treaties were signed, dozens of Saskatchewan First Nations did not get the amount of land they were promised for their reserves. For other First Nations, their land was given to them, but then the government took it back to build infrastructure, give it to white farmers, or give it to white veterans coming back from the First and Second World Wars.

First Nations are now talking about “specific claims” to get back what they were promised by picking out pieces of Crown land. If the building has already been sold, they can’t do that.

Sheldon Wuttunee, the CEO of the center, said that Lewis and other people have a right to be worried. He said that we need to act quickly.

“Early on, Crown lands were set aside to make sure that the Crown was able to keep their treaty agreements, so that we could hunt, fish, trap, gather, and use our treaty rights as long as there were Crown lands to do so. So it’s very scary when Crown lands and minerals are sold off at an alarming rate, Wuttunee said.

Wuttunee’s group has also made maps of claims and places where oil, potash, and even important minerals like lithium can be taken out. He said it’s important for First Nations to know what’s going on above and below the ground.

Betty Nippi-Albright, the First Nations and Métis Relations critic for the opposition NDP, has been pushing the government on this issue for years. She said that the Constitution says First Nations have the right to be consulted on land and resource issues that affect them.

The Supreme Court has said this more than once, and she said that the government is not doing its legal job.

“So, we’ve been talking about the sale of Crown lands and leases without consultation, and when there has been consultation, the process has been very quick. Nations must be asked what they think. “They need to be asked right away,” she said.

Agriculture Minister David Marit was not available for an interview, but a government official emailed a statement on his behalf.

It said that the government “seeks information from potentially affected First Nation and Métis communities about how they use the land for hunting, fishing, trapping rights, and traditional activities.” If the land is needed for these things, the government doesn’t sell it.

Lewis, Quinney, Wuttunee, and others say that Marit’s words don’t match up with what the government is doing. They say that this is not being done at all.

Quinney said that government officials often say things that aren’t true. Some people say that they talk to the First Nation if the land is within 60 kilometers. Another official said it’s between 75 and 100 km. She said that in reality, they often don’t even talk to First Nations about land that is next to them.

Quinney said that this could end up in court. She said that First Nations will go to court with their maps if they have to.

She said, “They just pick and choose who they want to talk to.””They’re going back on what they said.”