Experts say there is a mismatch between the services cities offer and the money they can bring in

The rise in money going into the Ontario government’s coffers, which is happening at a time when municipal budgets are already tight, is bringing up the question of how cities pay for their services again.

Municipal finance and public policy experts say that the services cities are expected to provide don’t match up with the money they have to pay for them.

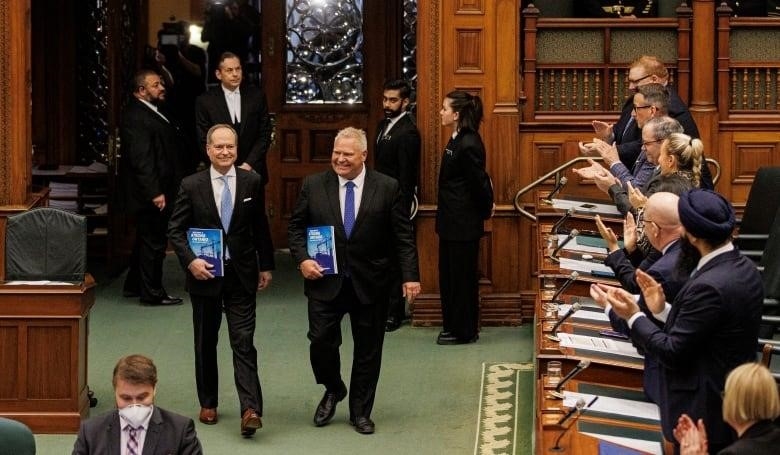

This difference is made clear by new numbers in the budget that Premier Doug Ford’s government put forward last week. These numbers show how rich the province is right now:

- Between 2019 and 2022, the amount of tax money collected from corporations went up by a huge $12.5 billion, or 81%.

- In the same three-year period, personal income tax revenue rose by $15 billion, which is a 40% increase.

Compare this to the much slower growth of municipal revenue: from 2017 to 2021, the latest year for which data is available, property tax revenue into all of Ontario’s more than 400 cities and towns only went up by $3.5 billion. That’s an increase of 17% in just four years.

Sunil Johal, a professor of public policy and society at the University of Toronto, says that cities in Ontario have a lot more responsibilities than they can pay for.

“Municipalities can’t make any more money, but the costs that have been put on them keep going up and getting more complicated,” Johal said in an interview.

Even though cities have had money problems before COVID-19, the pandemic has made things worse, says Johal.

He said, “They’ll have to make very hard decisions about cutting services at a time when so many people need so many of those services.”

“We need to think about a long-term solution to a problem that is only getting worse and more important.”

In Ontario, municipalities provide not only local services like police and fire protection, public transportation, water, sewers, and trash collection, but also public health, social housing, and shelter for the homeless.

Enid Slack, who runs the Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance at the University of Toronto’s School of Cities, says that cities have “huge costs but very few ways to pay for them.”

Slack says it’s time for a new conversation about how the province and local governments share responsibilities and how to pay for the services they provide.

“Cities, especially Toronto, are facing a lot of problems,” Slack said. He mentioned inflation, high interest rates, crumbling infrastructure, population growth, and the lingering effects of the pandemic, which affect both the number of people who take public transportation and the number of people who need social services.

She said, “We need to make sure that the cities’ sources of income are in line with what they spend.” “So, if we decide that social services are best handled by cities and towns, we need to give them the money they need to do their jobs.”

The last full-scale review15 years ago, there was a change in how cities and towns in Ontario get their money.

It’s not clear that the Ford government is ready to start talking about this.

CBC News asked Finance Minister Peter Bethlenfalvy if the fact that cities are short on money means that there needs to be a big change in how cities are paid for.

Bethlenfalvy replied by talking about how he planned to spend $1 billion in new money over the next three years.Homelessness, mental health, and drug and alcohol abuse. He also brought up the third-party audits that the government plans to do in some large cities.

Bethlenflavy said that cities and towns need to take part in the conversation about a financial framework.

“We sit down with them and look at their books together to ask, “All right, what are the pressures?” What problems need to be solved? And how can local, provincial, and federal governments work together to make a framework that will last?'”

But the audits don’t at all cover everything about how a city or town handles its money. The focus is on how cities and towns use their reserve funds and how they handle development charges, which are fees put on building projects to help pay for new infrastructure.

The Association of Municipalities of Ontario (AMO) thinks that the restrictions on development charges put in place by the government’s Bill 23 will cost cities about $10 billion over the 10 years of the province’s “More Homes Built Faster” housing supply action plan.

The executive director of AMO, Brian Rosborough, said, “Municipalities would love to talk to this government about the fiscal framework.”

“We’re open to either increasing spending on services that are in high demand, like social housing and homelessness, or changing the way money is spent so that some of the responsibility for those things goes back to the province,” Rosborough said.

AMO’s top priority was to make a deal with the province that is “stable, sustainable, and affordable for property taxpayers.”requestTo the political parties in Ontario during the election campaign last year.

In all of this, there is one big question: Do cities need to be able to charge a wider range of taxes, like income tax or sales tax?

In a reportIn a report that came out a year before the pandemic, researchers at the now-closed Mowat Institute, an Ontario public policy think tank, said that cities needed to find new ways to make money so they didn’t have to rely so much on property taxes.

Slack says that income tax is a better way to spread wealth around than property tax.

“Property tax isn’t always the best way to pay for things like social services, housing for the homeless, and other similar services,” she said. “An income tax is more appropriate.”

Since 2016, the City of Toronto’s total property tax income has gone up by an average of less than 3% per year.

The city of Toronto’s annual financial report for 2020 said, “Property taxes continue to be one of our sources of revenue that grows the least.”