In the last week of June, 339 calls to Provincial EMS were related to opioids

Alberta Premier Danielle Smith said Thursday that her government is thinking about what to do about the addition of animal tranquilizer to opioids and the rise in overdose deaths.

Smith said, “I have a team working on this, led by [Minister of Mental Health and Addiction] Dan Williams, to see if there is anything else we can do from a therapeutic point of view to look at this new combination.”

“This is what the answer is. We don’t think it’s possible to have a safe supply of opioids.”

The province’s system for keeping track of drug use released new numbers on Wednesday, which prompted the premier to say something.

During the week of June 26, 339 EMS calls in Alberta were related to opioids. This is the most since the province started keeping track of data.

The previous record was 277 calls, which was set the week before.

It’s making it hard for people who work on the street with drug addicts, like the non-profit Streets Alive Mission in Lethbridge, to do their jobs.

“It’s not surprising at all,” said Cameron Kissick, who is in charge of operations at Streets Alive.

“This is the worst it’s ever been. But this has been getting worse… It’s getting worse and worse.”

Xylazine, which is often called “tranq dope,” has been found in drug supplies across North America in the past few months.

People who touch xylazine can lose consciousness and get painful wounds that, in rare cases, may need to be cut off. Naloxone, a drug that can reverse an overdose and save a person’s life, cannot reverse the effects of xylazine.

“There’s pretty much xylazine in everything. “I don’t think we’ve seen fentanyl that doesn’t have xylazine in it very often,” Kissick said.

“I can’t speak for other organizations or for Lethbridge as a whole, but we see overdoses every day, if not more than once.”

Overdose deaths hit recor

According to the province’s substance use surveillance system, 179 people in Alberta died of opioid poisoning in April. This is the most since the province started keeping track of this data seven years ago.

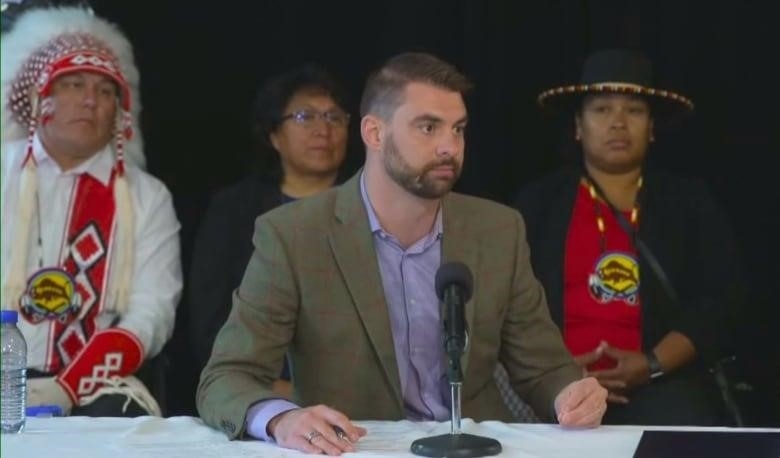

Alberta’s minister of mental health and addiction spoke at a provincial announcement Thursday about a memorandum of understanding signed with Siksika Nation to build a new recovery community with 75 beds. Williams said that the next steps were being thought about, especially from a therapy point of view.

“In the long run, we need to get these rehabilitation centers up and running. We need to keep working on a recovery plan. “The Alberta Model is not trying to hide from the fact that the number of addicts is going up,” Williams said.

“We know that when someone is addicted to opioids, there are two possible outcomes: tragedy, with an emergency response and hopefully a life saved from an overdose, or recovery. There are only two ways out.”

Elaine Hyshka, an associate professor at the University of Alberta School of Public Health and the Canada Research Chair in health systems innovation, said that the recent EMS numbers are scary. She said that her coworkers who work in front-line services feel like they’re “drowning.”

“I think it’s very unfair to give these life-saving emergency responses to other people. In some cases, someone is called to five or six overdoses in one shift, in a community, in a bathroom, or in an alley. “That won’t work in the long run,” she said.

“People who are having trouble also deserve more than that.”

Hyshka said that the problem on the streets right now means that people can’t wait years for the promised recovery solutions to be built.

“Right now, we need a response to the emergency that includes making things safer. She said, “I just don’t know how to say that more clearly.” “It’s not about getting better or reducing harm. “Yes, and no.”

WATCH | A group that reaches out to addicts goes out on the street to help them get through the opioid crisis: