Researchers say that more research needs to be done near cemeteries

WARNING: This story has parts that are sad.

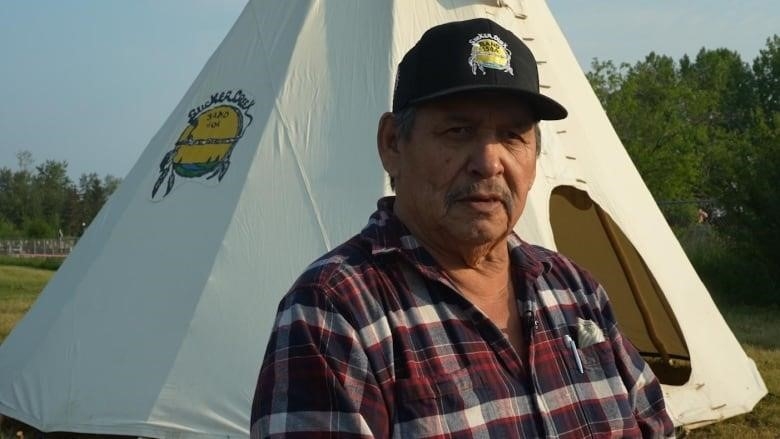

Sucker Creek First Nation Chief Roderick Willier remembers that he never felt safe at a residential school in northern Alberta where he spent ten years.

“I always had to be on high alert when I was there,” Willier said about his time at St. Bruno’s Indian Residential School in Joussard, Alta., between the ages of 7 and 17. The school is about 335 km northwest of Edmonton.

“Oh, you have to be careful of them,” I was always told at residential school.

Researchers from the University of Alberta recently found signs that there might be 88 unmarked graves near the old school.

The search was led by Dr. Kisha Supernant, who said that the project focused on the areas that residential school survivors and community elders had pointed out.

With ground-penetrating radar, Supernant’s team looked over 4,500 square meters of land for pits or grave shafts.

She said that the team found signs of unmarked graves in two places outside of the school cemetery. One was near the school’s workshop, and the other was near a root cellar.

Supernant, whose family is from Joussard, said that the research team thinks graves found outside of a cemetery on the school grounds should be looked into more.

“What’s happening here? “Why are there graves in these places that are not known to be cemeteries?”

Professor of anthropology at the University of Alberta Talisha Chaput warns that the ground-penetrating system doesn’t give a lot of information.

Chaput said that there are other ways to find out if the graves are there or not.

“One way to look under the ground is with a ground-penetrating system.She said, “This technology is not the end of everything.”

Other ways to find out if the possible graves are there are through testimonies, historical records, and records of students who went to school. The unmarked graves could also be found by digging or sending trained dogs to smell human bones buried in the ground.

But Chaput said that digging is against what most First Nations people believe.

“Most people think that once someone is buried, you shouldn’t bother them again,” she said. “Even though there may be times when it can’t be helped.”

The people in Joussard haven’t decided what they’ll do next to make sure the graves are real.

On Saturday, more than 1,100 people from the town of Joussard came together for a blanket ceremony to honor the people who may be buried in the unmarked graves.

Shane Pospisil, executive director of the Lesser Slave Lake Indian Regional Council, which represents a number of First Nations around Lesser Slave Lake in Alberta, said, “People were wrapped in the blanket and cuddled in that blanket to show compassion, care, and love.”

He said that people in the town are feeling a lot of different things. There are a lot of tears and smiles, and for some, it’s just another day in town.

Pospisil said that the community will look for more unmarked graves over the next two years, even on land that they couldn’t get to last summer.

Supernant said that it is hard for First Nations communities to get to the land. Some old school buildings have been torn down and replaced with new ones, while others have been bought by private landowners.

“This is very hard because the schools were built on very large pieces of land. “And there are a lot of places to look,” she said.

“Something we won’t be able to forget.

For Willier, the chief of Sucker Creek First Nation, it’s all about moving forward and healing as a community while still remembering the past.

“Right now, we have to teach our kids about this because we can’t forget.

There is a national Indian Residential School Crisis Line that can help survivors and others who were affected by the schools. People can get emotional and crisis referral services by calling 1-866-925-4419, which is open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

The Hope for Wellness hotline at 1-855-242-3310 or online chat is also open 24 hours a day, seven days a week for mental health counseling and crisis support.

This story was made possible by a grant from the Meta and Canadian Press News Fellowship, which had nothing to do with how it was written.